We have reached an endpoint of sorts in the decade-long Afghanistan War. President Obama will not keep U.S. troops in Afghanistan to defeat the Taliban and force them to accept terms of any kind. Have we lost the war? Should we have left years ago, or never gone in? That depends on your view of what we were fighting for and about in the first place.

I. Lowering The Bar

Gone is the much greater expectation that NATO will leave behind a cohesive central government with real influence beyond Kabul and a handful of other population centers. Gone is the assumption that Helmand Province, Kandahar and the rest of the heavily contested south – where the bulk of the 2010 influx of troops was sent – will remain entirely in the control of the central government once that area is transferred to Afghanistan’s fledgling national security forces.

…President Obama’s national security adviser, Thomas E. Donilon, described a hoped-for outcome in Afghanistan that was far less ambitious than what American officials once envisioned.

“The goal is to have an Afghanistan again that has a degree of stability such that forces like Al Qaeda and associated groups cannot have safe haven unimpeded, which could threaten the region and threaten U.S. and other interests in the world,” Mr. Donilon said.

Nowhere on this list is the defeat of the Taliban, which – seeing this coming – gave up on peace talks months ago:

While Kandahar and other population centers in the south have seen a decrease in Taliban attacks since the surge forces arrived, insurgent attacks have increased in less populated southern areas, military officials report. The heads of the Senate and House intelligence committees, appearing on CNN’s “State of the Union” program two weeks ago, and reporting on a recent trip to Afghanistan, said the Taliban were gaining ground, something that is bound to accelerate once the NATO troops give way to Afghan-led forces.

“I think we’d both say that what we found is that the Taliban is stronger,” Senator Dianne Feinstein, Democrat of California, said, seated next to Representative Mike Rogers, Republican of Michigan.

As Dan Spencer noted yesterday, this is a distinct change of tune from 2008, when then-candidate Obama described Afghanistan as “a war that we have to win” and 2009, when President Obama declared:

This is not a war of choice. This is a war of necessity. Those who attacked America on 9/11 are plotting to do so again. If left unchecked, the Taliban insurgency will mean an even larger safe haven from which Al Qaida would plot to kill more Americans.

So this is not only a war worth fighting; this is a – this is fundamental to the defense of our people.

But despite the President’s bold words, the Administration never did set a clear definition of victory in Afghanistan. Specifically, while the State Department designated the Pakistani Taliban a terrorist group, it resisted requests by even Democratic Senators to designate the Afghan Taliban as a terrorist group, apparently – at the time – due to an unwillingness to foreclose a negotiated resolution that would bring the Taliban back into the political process. This was not a new problem (the State Department had likewise refused to designate the Taliban as a terrorist group during the Bush Administration even in 2001) but at a time when the nation was ramping up its military commitment to the war in Afghanistan, the broader refusal to define an enemy to be defeated (the essential element of any military action) left the war effort directionless and increasingly difficult to justify to a war-weary public. And now, by withdrawing unilaterally without using the leverage of our arms to force a negotiated resolution on favorable terms, we are essentially washing our hands of the fight against the Taliban.

II. A Premeditated Retreat

David Sanger in the NY Times looks at how President Obama came to this pass. He starts with the 2009 announcement of a ‘surge’ in Afghanistan that President Obama had reluctantly agreed to after months of requests from the military leadership and which was sold to the public in large part on the basis of the credibility of the military brass:

The aide told Mr. Obama that he believed military leaders had agreed to the tight schedule to begin withdrawing those troops just 18 months later only because they thought they could persuade an inexperienced president to grant more time if they demanded it.

“Well,” Mr. Obama responded that day, “I’m not going to give them more time.”

A year later, when the president and a half-dozen White House aides began to plan for the withdrawal, the generals were cut out entirely. There was no debate, and there were no leaks.

So much for the views of the commanders on the ground; so much for flexibly or pragmatically re-evaluating the situation; so much for victory. Obama had “narrowed the goals in Afghanistan, and narrowed them again, until he could make the case that America had achieved limited objectives in a war that was, in any traditional sense, unwinnable”:

“I think he hated the idea from the beginning,” one of his advisers said of the surge. “He understood why we needed to try, to knock back the Taliban. But the military was ‘all in,’ as they say, and Obama wasn’t.”

…By early 2011, Mr. Obama had seen enough. He told his staff to arrange a speedy, orderly exit from Afghanistan. This time there would be no announced national security meetings, no debates with the generals. Even Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates and Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton were left out until the final six weeks.

The key decisions had essentially been made already when Gen. David H. Petraeus, in his last months as commander in Afghanistan, arrived in Washington with a set of options for the president that called for a slow withdrawal of surge troops. He wanted to keep as many troops as possible in Afghanistan through the next fighting season, with a steep drop to follow. Mr. Obama concluded that the Pentagon had not internalized that the goal was not to defeat the Taliban.

As Jonathan Tobin notes in Commentary:

[I]t is now apparent that the administration lacked the one thing any country needs in war: a commitment to victory. Without it, the Afghan surge was just a blip on the radar screen and, unlike the Iraqi insurgents who knew President Bush meant business during the U.S. surge in that war, the Taliban were right to discount the possibility that President Obama was just as tough-minded. Even at the outset of the new surge it’s clear now the president saw it as merely a bloody prelude to a withdrawal with, as Sanger notes, no provision for what would happen if the Taliban start their own surge after the Americans leave.

The administration gives itself credit for having rethought strategy and concentrated instead on the real “good war” – fighting al-Qaeda in Pakistan. But if, as Sanger reports, the administration had concluded that there had never been a coherent U.S. strategy in Afghanistan, the same is certainly true of American objectives in Pakistan. In truth, the U.S. has no strategy in Pakistan other than to keep attacking terrorists in the tribal areas with drones, a tactic that is deadly but has no chance of ridding the area of trouble or maintaining Pakistan as an ally in the war against the Islamists. The only thing that recommends this plan is that it requires few American troops and allows the president to adopt the “lead from behind” posture with which he is so comfortable.

President Obama’s 2009 decision to stay the course in Afghanistan and use a surge to fight the Taliban was the sort of responsible action that gave the lie to his detractors’ assertion that he had little understanding of the strategic imperatives of fighting the country’s Islamist foes. But, as we now know, the applause he earned then was largely undeserved. His only real goal was to bug out of Afghanistan but to do so without having lost the country before he ran for re-election in 2012.

This approach is terribly damaging to American credibility, which requires that our allies and enemies alike understand that we finish what we start. However bad Obama’s options, he is choosing a path that has emboldened our enemies in the past, most notably Osama bin Laden’s famous conclusion from American retreats from Vietnam, Lebanon and Somalia (each, perhaps, individually defensible in a way) that America was not the ‘strong horse’ and could be easily waited out.

III. What Were We Fighting For?

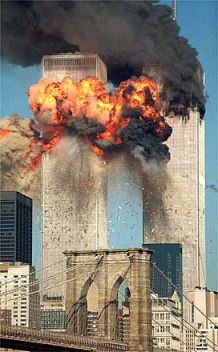

The Afghanistan War began, of course, with the September 11 attacks. As I have previously noted, there were always three war aims:

1. Drive the Taliban, which had supported and sheltered Al Qaeda, from power.

2. Destroy Al Qaeda’s training and operations bases in the country, while killing or capturing as many of their personnel as possible.

3. Replace the Taliban with a government that was less repressive, viewed as legitimate by the Afghan people, and would not cooperate with Al Qaeda – a step that inherently involved preventing the revival of the Taliban itself, given its Islamist ideology and thorough integration with Al Qaeda.

Step One was accomplished swiftly in the fall of 2001, and Step Two proceeded apace at the same time; Al Qaeda’s leadership was never wholly destroyed (after the November 2001 Battle of Tora Bora, the very top senior leadership fled the country, with Osama bin Laden ending up in Abbottabad, Pakistan, where he was tracked down and killed in May 2011), nor completely routed from the country, but its bases were destroyed and its ability to project power from Afghanistan to outside countries was essentially crippled. Afghanistan by itself has never been a threat to the United States, and since 2002, Al Qaeda has been unable to use the country to project threats outside of its immediate neighborhood. By that measure, victory was already in hand a decade ago, much as our original mission in Iraq was accomplished once Saddam Hussein’s regime was toppled.

Step Three was always the diciest as a long-term proposition; as I wrote in early 2003:

Long-term, we would like to establish a secure government in Afghanistan that will consolidate the victory over theocracy and prevent re-establishment of havens for terror. But if we fail in that aim, as we still may, the war will no more be a failure than it is a failure to weed your garden in spring and, the following year, discover new weeds.

Where to go from driving the Taliban from power? The Bush Administration had a short and medium-term strategy, but never really answered that question in the long term. Republicans and conservatives (including Bush, vocally in the 2000 campaign and throughout his presidency when facing calls for interventions in places like Liberia) have generally been opposed to sending troops to foreign lands for “nation-building” purposes, but there is a certain amount of wisdom to Colin Powell’s “Pottery Barn rule” (you broke it, you bought it): if you topple a foreign government by force, it is wise and arguably a responsibility to stick around long enough to have some say in what replaces it and try to prevent another hostile regime from being formed. This was the analogy drawn from successful ‘nation rebuilding’ in Germany and Japan after World War II. And that, at first, was what we did in Afghanistan: help Hamid Karzai form a new government, hold (at the time) reasonably free and fair elections for president in 2004 and the parliament in 2005, engage in combat to defend against threats to the formation of a democratic government, and add in some public works, education and other public-diplomacy endeavors to encourage the Afghans to stick with the new system. More controversially, the Bush Administration treated both the Afghan and Iraqi theaters as opportunities to put on something of a demonstration project on democracy and civil liberty in the Islamic heartland in the hopes of inspiring Muslims across the region to prefer alternatives to tyranny and take responsibility for their own countries’ problems rather than persisting in projecting violence towards the U.S., Israel and the West as a proxy for addressing their own societies’ failures.

At the time, Democrats blasted the Bush Administration and Defense Secretary Don Rumsfeld in particular for preferring a “light footprint” in Afghanistan rather than directing more troops to the country. Much of this argument, in its day, involved Monday morning quarterbacking of the Battle of Tora Bora, but a decade on, the debate specific to Tora Bora and the original invasion strategy no longer has much public policy salience and can be best left to the military historians to judge. And ironically, President Obama has now come around to claim ownership of a version of the (at least stereotypically) Rumsfeldian view of a mobile, quick-strike, shock-and-awe military heavy on technology and light on ‘boots on the ground’ nation-building:

Out of the experience emerged Mr. Obama’s ‘light footprint’ strategy, in which the United States strikes from a distance but does not engage in years-long, enervating occupations. That doctrine shaped the president’s thinking about how to deal with the challenges that followed – Libya, Syria and a nuclear Iran.

On the specific question of nation-building, it is hard today to find anyone who thinks America has not done enough in Afghanistan. We have bled a decade of young men and women and expended much treasure in exchange for little gratitude. The Karzai government has been an improvement in most every way over most Afghan governments in recent memory, but by any measure – commitment to free and fair elections, civil and religious liberties, resisting corruption, providing security to its people and a loyal ally to the United States – it has fallen far short of the standards set by even second-rate members of the community of free nations. Americans in the Afghan theater have many tales of betrayal by our putative Afghan allies, and a March massacre of 16 civilians by a U.S. soldier has exacerbated the problem.

Winning Afghan hearts and minds always faced some daunting obstacles that are best illustrated with a few facts:

1. The median age in Afghanistan (for both men and women) is 18.2 years. 42% of the population is age 14 or younger. Male life expectancy is 48.45 years.

2. 56.9% of Afghan men over age 15, and 87.4% of Afghan women, are illiterate.

3. Less than a quarter – 23% – of the population is urbanized, compared to 66% in Iraq.

4. In one highly-publicized poll taken a few years ago in the southern Kandahar and Helmund provinces of Afghanistan by the International Council on Security and Development, 92% of Afghan men claimed never to have heard of the September 11 attacks. While it’s not clear how reliable this particular finding is, other polls have tended to show a good deal of public hostility in that region to military efforts to defeat the Taliban (see here, here and here).

In short, the average Afghan in the countryside – constituting most of the population, unlike in Iraq – isn’t old enough to remember why the United States went to war in their country more than a decade ago, and a largely ignorant and illiterate population is deeply disconnected from any concerns outside their immediate neighborhood.

After Iraq, the attention of the Islamic world has moved on to popular movements of various stripes against entrenched tyrannies in places like Egypt, Syria, Libya, and Tunisia, some of those movements more promising or alarming than others, but all of them reflecting that the genie of destabilizing revolutions is now out of the bottle for good or ill. We have given the Afghan people plenty of chances to build, as Ben Franklin would say, a republic, if they could keep it. And we have done all we need to do in Afghanistan to encourage a process of change across the Islamic world that is now mostly beyond our control. If we are to stay in Afghanistan for some purpose, it must not be simply nation-building or demonstration of the value of alternatives to Islamist government. It must be the defeat of a defined enemy. And that means that if we stay, we stay to battle the Taliban.

IV. Should We Let The Taliban Go?

This brings us to the core of the problem. On the one hand, when last in office, the Taliban was effectively organizationally indistinguishable from Al Qaeda, giving it safe haven and relying on it for security assistance; that was why Mullah Omar’s government was unwilling to turn over Al Qaeda’s leadership even when the alternative was a U.S. invasion. In practice, Taliban governance was the harshest possible form of Islamist theocracy, putting the leadership in ideological sync with the most virulent elements of Islamist terrorism. There is no way to be certain that a reconstituted Taliban, victorious after a decade fighting the U.S., would not reopen its alliance with Al Qaeda (although one could argue, as I did in 2003, that we should just return when we see that happen). There is certainly no reason to think the Taliban have changed their brutal ways.

On the other hand, 42% of the population of the country – Afghanistan’s largest ethnic group – is Pashtun, and there is effectively no other political organization that rivals the Taliban for representation of Pashtun interests. In a tribal society, that is an unbreakable hold. This is why – as is often the case in civil wars – some form of political accomodation with some political organ that includes much or all of the Taliban’s constituency and probably a good deal of its personnel is perhaps inevitable. But a U.S. departure without engagement in the process of forcing the Taliban to accept coexistence with the rest of the country’s factions leaves the enemy in the field on its own terms and in a position to declare victory.

As I think the foregoing should illustrate, the problem of how to define victory in Afghanistan is a hard one; it bedeviled the Bush Administration after the 2004 and 2005 elections there marked the end of the low-hanging fruit of nation-building. Mitt Romney has proposed thus far that we remain flexible and listen to the commanders on the ground, which is better than ignoring them but not really a clear answer either to what our endgame is intended to be (not that Romney will have much control over the evacuation by next January, even if he wins the election). So, unlike the decision to get Osama bin Laden, this is not an easy call for Obama.

But President Obama’s unwillingness to back up his own public pronouncements of the importance of the war, to listen any further to the generals, to consider further the conditions on the ground, or to require that any real progress be made against the enemy before abandoning Afghanistan illustrates Obama’s limitations as Commander-in-Chief. His record on national security has not been an unbroken record of disaster but a mixed bag with some successes and more than a few pleasant surprises in his willingness to walk away from ridiculous campaign promises. But where Obama has succeeded, he has mostly done so either by doing nothing or by staying the course of directions set in the Bush years. Asked to actually set a meaningful new direction or expend scarce political capital even on an ongoing shooting war, his instinct is to first procrastinate, then kick the can down the road for a while, and ultimately throw in the towel. Rousing the nation to take controversial actions is above his pay grade.

The choices before us are indeed difficult. But we have abandoned Afghanistan before, and lived to regret it. Let us hope that we do not again.

This is another item that will be shot down the rabbit hole for another 4-5 years. Obama should not have delayed his Afgan surge decision and should have brought the boys home after OBL’s death. Perfect opportunity with opinion polls in his favor for that move had he done it. It also would have made sense as I dont think anyone knows what we’re doing in Afganistan anymore.

Another roadblock in nation building in Afganistan is the extremely high rate of cousin marriage. North of 50% per reliable studies.

Crank,

Excellent post! Well, if the world were a seminar and we could simply ignore all the, um, inconvenient facts concerning the chaos left by the previous administration and the consequences of its disastrous choices, it would be an excellent post.

Still, as fiction, it ranks up there with the best of Faux News.

If the only thing we had going on was a war on the Taliban in Afghanistan, I could tolerate sticking it out and wiping them out. But we’ve already had Iraq, and as you note, we have Islamists in Pakistan, and let’s not forget about Iran, and well, half the rest of the Middle East as well.

As far as I’m concerned we’ve sent enough of a message: if you support a group that bombs our buildings, we’re coming after you. We’ve done that, we’ve kicked them out, we’ve extracted a big toll on their organization, and there is at least a new government in place, however imperfect. Now it’s their turn fix everything else that is wrong with Afghanistan.

If entitlement spending doesn’t do it first, this urge to engage in widespread nation-building in the Middle East will bankrupt us. The analogy between Germany and Japan after WWII is poor. Germany and Japan had far more developed economies and relatively homogenous populations. Most of the Middle East, by comparison, is a hornet’s nest of economic weakness, poverty, hostile ethnic factions and religious extremism.

If the only thing we had going on was a war on the Taliban in Afghanistan, I could tolerate sticking it out and wiping them out. But we’ve already had Iraq, and as you note, we have Islamists in Pakistan, and let’s not forget about Iran, and well, half the rest of the Middle East as well.

As far as I’m concerned we’ve sent enough of a message: if you support a group that bombs our buildings, we’re coming after you. We’ve done that, we’ve kicked them out, we’ve extracted a big toll on their organization, and there is at least a new government in place, however imperfect. Now it’s their turn fix everything else that is wrong with Afghanistan.

If entitlement spending doesn’t do it first, this urge to engage in widespread nation-building in the Middle East will bankrupt us. The analogy between Germany and Japan after WWII is poor. Germany and Japan had far more developed economies and relatively homogenous populations. Most of the Middle East, by comparison, is a hornet’s nest of economic weakness, poverty, hostile ethnic factions and religious extremism.