RS: The Breakers Broke: A Look Back At The Fall 2014 Polls

As promised in my first cut after the election, a more detailed walk by the numbers through the 2014 Senate and Governors race polling and my posts on the subject to illustrate that the election unfolded pretty much along the lines I projected on September 15, when I wrote that “[i]f…historical patterns hold in 2014, we would…expect Republicans to win all the races in which they currently lead plus two to four races in which they are currently behind, netting a gain of 8 to 10 Senate seats.”

This was not a consensus position of the models projecting the Senate races at the time; Sam Wang, Ph.D. wrote on September 9 that “the probability that Democrats and Independents will control 50 or more seats is 70%” and described a 9-seat GOP pickup as “a clear outlier event.” On September 16, the Huffington Post model had a 53% chance of the Democrats keeping the Senate, while the Daily Kos model on September 15 had the Democrats with a 54% chance of retaining their Senate majority. Nate Cohn at the New York Times on September 15 gave the GOP just a 53% chance of adding as many as 6 seats, with Republicans having just a 35% chance of winning in Iowa, 18% in Colorado and 18% in North Carolina, and a 56% chance of winning in Alaska. The Washington Post on September 14 had the Democrats favored in Alaska, with a 92% chance of winning Colorado and a 92% chance of winning North Carolina. Even Nate Silver and Harry Enten’s FiveThirtyEight Senate forecast, which was more optimistic than some of the others for Republicans at the time, gave the GOP just a 53% chance of making it to a 6-seat gain as of September 16.

In this case, at least, my reading of history was right, and was a better predictor of the trajectory of the race than the models or the contemporaneous polls they were based on. That won’t always be true; it wasn’t in the 2012 Presidential race. It may or may not prove true in the 2016 Presidential race, where the historical trends overwhelmingly favor Republicans. But after 2012 we were greeted with an onslaught of triumphalism for polls, poll averages and poll models, and what 2014 illustrates is not only that – as we already knew – the models are only as good as the polls, but also that there remains a place for analysis and historical perspective and not just putting blind faith in numbers and mathematical models without examining their assumptions (a point that some of the more cautious analysts, like Silver and Enten, tried to their credit to stress to their readers during the 2014 season).

It also validates my broader view that subjects like polling are best understood when you have an adversarial process of competing arguments rather than deference to a consensus of experts. Because poll analysis down the home stretch involves a high degree of emotional involvement in partisan wins and losses – and most people who get involved in arguments about polling have strong partisan preferences – it’s next to impossible to avoid the pull of confirmation bias, the tendency to credit arguments you want to see win and discredit those you want to see defeated. Certainly mathematical models and poll averages can offer a check against bias, but inevitably they also rest on assumptions that incorporate bias as well. It remains broadly true, as I pointed out repeatedly in and after the 2012 election, that liberal poll analysts and Democratic pollsters tend to do a better job in years when Democrats do well, and that conservative poll analysts and Republican pollsters tend to do a better job in years when Republicans do well, because in each case they are more likely to credit the assumptions that prove accurate. Nate Silver just published a fascinating post on how the 2014 pollsters tended to “herd” towards each other’s results, which tends to exacerbate the problem of being skewed in one or another direction in any given year – more proof of streiff’s view of the herd mentality of pollsters and Erick’s view of polls weighting towards 2012 models without an adequate baseline, and another strike against expert “consensus” thinking and in favor of the virtues of examining your assumptions. The best corrective for the reader to apply to these biases is to listen to both sides, examine the plausibility of their assumptions, and then go back later and evaluate their results.

The Theory

As you may recall, my underlying theory of the 2014 election germinated with the work of Sean Trende of RealClearPolitics, who set out the argument as far back as January 2014 that Obama’s low job approval would exert a gravitational pull on Democratic Senate candidates:

If the president’s job approval is still around 43 percent in November — lower than it was on Election Day in 2010 — the question would probably not be whether the Democrats will hold the Senate, but whether Republicans can win 54 or 55 seats. Given the numbers right now, that should not be unthinkable.

Trende followed this with a more detailed analysis in February that had Democrats likely to lose 8-10 seats if Obama’s approval rating was in the low 40s, then in late August noting that undecided voters in the polls were disproportionately voters who disapproved of Obama, then on September 4 arguing that “Democrats are winning over the voters who approve of Obama, and not much more…undecided voters have not yet engaged fully with the process. When they do engage, Obama’s unpopularity will make it unlikely that they will vote Democratic,” and on September 25:

If this theory is right, we should expect to see these races continue on the basic trajectory we’ve seen over the past few weeks: Democrats holding at their current levels. Eventually, Republicans should begin or continue to improve, as undecided voters engage and make up their minds, and as Republicans narrow the spending battles. Even if this theory is true, it won’t occur in every race, but it will be the general tendency.

As it turned out, Obama’s approval rating on Election Day was either 42% (if you credit the RCP average) or 44% (if you credit the national exit polls), and assuming that Mary Landrieu loses her runoff in Louisiana (as seems likely – the top two Republican candidates beat her 56% to 43% on Election Day, the national party has stopped running ads for her, and the one partisan Republican poll out on the race so far has her down 16 points to Bill Cassidy), we’ll have a 9-seat GOP pickup to 54 seats.

My own work built on this, starting with my first roundup on June 26 (shortly after most of the big primaries had wrapped up) that sketched out a range of possibilities from a six-seat to a twelve-seat GOP pickup, with nine tight Senate races: Louisiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, Alaska, Iowa, Colorado, North Carolina, Georgia, and Michigan. I wrote then that “[i]f the national environment really does show as sour across the board for Democrats in November as it looks from today, eight-for-nine or nine-for-nine could be a possibility” – and while the bottom ended up dropping out of the Michigan race, Republicans did indeed go eight for nine.

My September 15 analysis added historical perspective: while the polls at that point had Republicans likely to gain six Democrat-held seats and hold all the Republican seats besides Kansas (at that point, [mc_name name=’Sen. Pat Roberts (R-KS)’ chamber=’senate’ mcid=’R000307′ ] was technically trailing but Chad Taylor had just dropped out of the Kansas race, so there wasn’t much reliable two-way Roberts v Orman polling), I argued that each of the last six Senate election cycles back to 2002 had taken place in “wave” conditions – i.e., the President’s approval rating and the generic Congressional ballot had both pointed in a direction that favored one party over the other – and that the party favored by the “wave” tended to win 3-4 races in which it still trailed in the mid-September polls, while almost never losing races in which it led at that point. That’s exactly what happened: Republicans won every race in which they led, plus Kansas, plus three races the Democrat still led in mid-September (Iowa, Colorado and North Carolina), plus making much closer races of two they still trailed badly in mid-September (New Hampshire and Virginia). Adopting Trende’s hypothesis that the main reason for this historical trend should be that undecided voters break towards the wave party, I started on September 26 in the Senate races and October 1 in the Governors races a “Breakers Report” that estimated – assuming each candidate held their current poll support on Election Day – what percentage of the remaining undecideds would need to break to the Republican to win.

Breaking The Polls

Now, in analyzing why we moved from moderately good polling news for Republicans in mid-September to outstanding news for Republicans when the actual votes were counted, it is debatable where movement in the voters ends and bad polling begins. There’s no dispute that the final polls were off, persistently in the direction of being skewed towards the Democrats, to a degree not fully explainable just by undecideds breaking (we’ll see some more granular evidence of this below). As I noted on Wednesday, one piece of that is that the polls were more skewed and less accurate – as Erick had speculated during the election – in states that didn’t have 2012 exit polls. Entertainingly enough, many of the poll analysts who didn’t buy into the “undecideds will break Republican” theory are now defending the polls by saying that…well, undecideds broke Republican. That’s what David Drucker reported in the Washington Examiner:

“What ended up happening very simply was that due to the national wave, all of the undecided voters broke for the Republican candidates,” said a Democratic strategist with regular access to internal polling.

…Peter Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Poll, noted that all of the undecided voters broke toward the Republicans over the final weekend of the campaign and emphasized that polling isn’t a perfect science.

It’s what Cohn saw as the most likely explanation in the election’s immediate aftermath:

The far likelier explanation, and one always allowed for, is that undecided voters broke towards the GOP

— Nate Cohn (@Nate_Cohn) November 7, 2014

Indeed, Cohn argues (with data) that Democratic voter-turnout efforts actually did a defensible job in improving the turnout of likely Democratic voters as much as could be expected, and while midterm turnout these days tends to favor Republicans, the problem was simply a failure to persuade the voters who decided these races: “If Democratic candidates like Ms. Hagan, Ms. Nunn, Mr. Braley and Mr. Udall needed a 2012-type electorate to win, then they were doomed from the start.” Mark Blumenthal and Ariel Edwards-Levy at Huffpost Pollster, in reviewing why the polls were skewed, noted that “[o]n average, across the nine most competitive Senate races, Republicans gained more than twice the support (+6.5 percentage points) as their Democratic opponents (+2.5 points) as the undecided vote steadily fell,” and notes as one possible explanation the theory that

[W]hatever vote remained undecided at the end of the campaign “broke” heavily or even entirely to the Republican candidates. “Often in wave elections,” Quinnipiac pollster Peter Brown explained, “virtually all the undecided or extra party voters go the same way.”

This theory works, at least in terms of simple arithmetic, in most of the Senate contests that produced the biggest errors on the margins. In Kentucky, Iowa, Georgia, Virginia, and Louisiana, allotting 80 percent of the undecided to the Republican candidate would reduce the error on their share of the vote to a percentage point or less. Of course, allotting nearly all of the undecideds to the Republicans also makes for an overstatement of their support in states where the polling was collectively accurate, such as Colorado, Alaska and New Hampshire.

Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy note that it’s equally possible that pollsters just got their turnout models wrong (Occam’s Razor suggests it was a mix of both), and also note that one of the polls with the persistently highest number of undecideds, YouGov, probably just overestimated how many “undecided” voters would actually vote. (Sam Wang, Ph.D., meanwhile, blames the polling failure primarily on the difficulty of modeling turnout in a low-turnout midterm, which is problematic given that we have midterms just as often as we have Presidential elections – more often, when you count odd-numbered-year races).

How They Broke

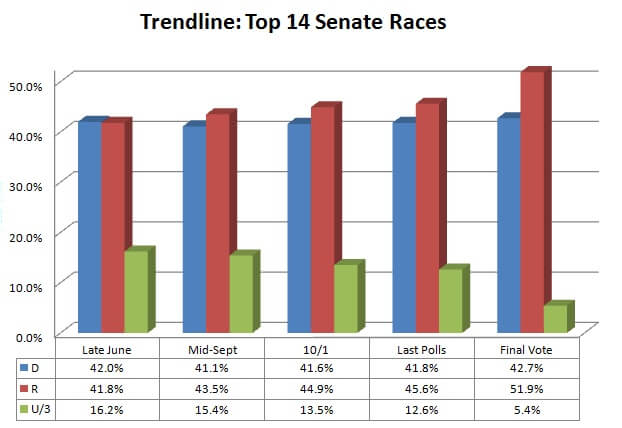

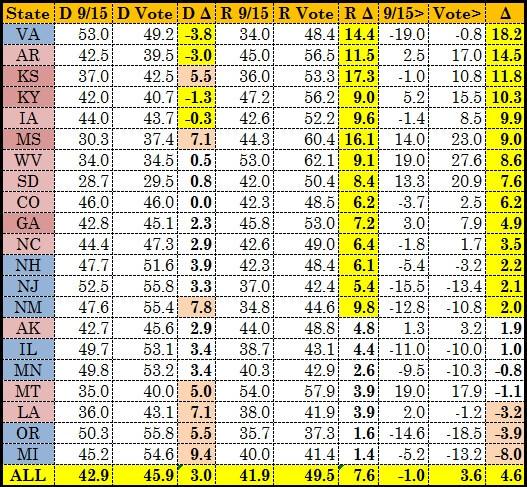

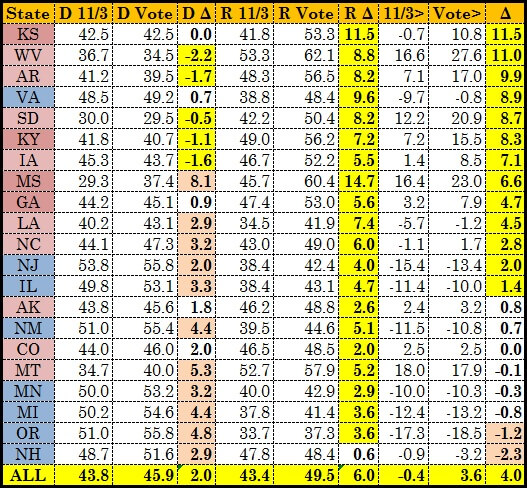

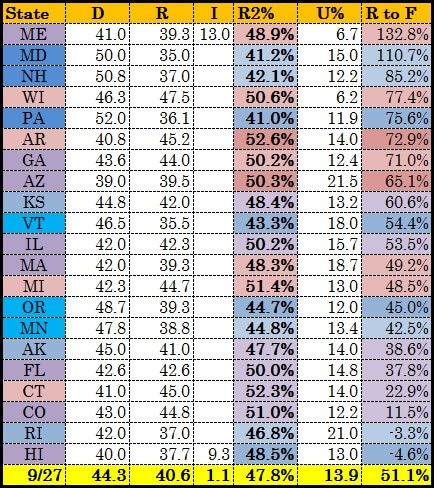

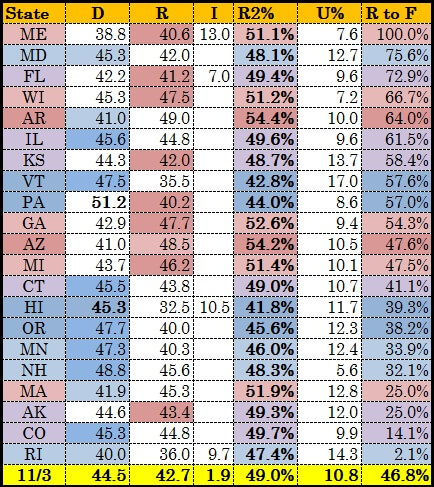

So, let’s just look back now at how the final results compare to the polls at differing junctures. The chart at the top of the page notes the trend across the 14 Senate races where Republicans were competitive or flipping a seat – the eight seats they gained already, plus Louisiana, plus the contested GOP-held seats (Kansas, Georgia, Kentucky), plus New Hampshire and Virginia. The trend – an unweighted average across those races – unfolds exactly as projected: Democrats holding steady from June to November and then just bumping up slightly as a share of the undecideds go their way in the voting booth, Republicans seeing undecideds break steadily their way all the way through the election. Here’s the trend across all the races I was following – those 14 plus Mississippi and six races the Democrats ended up winning handily – comparing the June 26 polling to the final results:

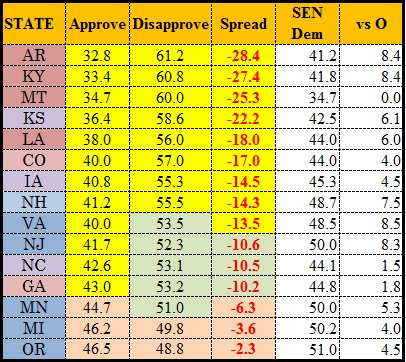

That’s a very dramatic break across the board, and it also illustrates (as do each of the subsequent charts) the failure of Terri Lynn Land in Michigan and Monica Wehby in Oregon, both of whom saw the voters break as heavily against them as the campaign proceeded as they were breaking against Democrats in most other states. Partly that’s Obama’s better approval ratings in those states combined with their residual partisanship, especially in Oregon where Gov. John Kitzhaber also got re-elected (granted, in a closer race at the end than the Senate race, as we’ll see below), but in Michigan, while Rick Snyder was gaining momentum in the Governor’s race, Rep. Gary Peters (D-MI), was stuck under 45% for so long that you have to believe the voters were just waiting for Land to give them a reason, any reason, to vote for her; she never did. Recall the final pre-election polls on Obama’s job approval in some of the key states:

Let’s run the same trend chart to compare the September 15 polls to the final results:

Louisiana looks low here in part because some of the late-breaking voters were breaking towards Maness rather than Cassidy. But the break was heaviest in states like Kentucky and Arkansas where – surprise! – President Obama is most unpopular.

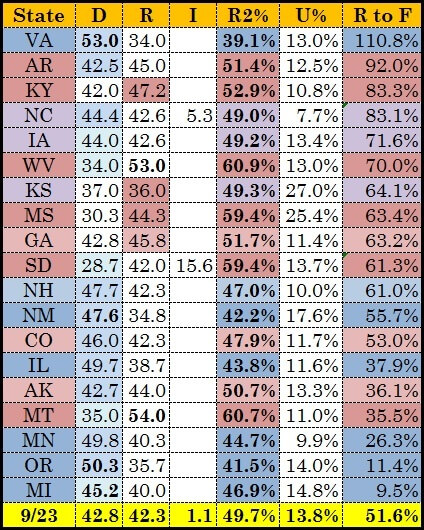

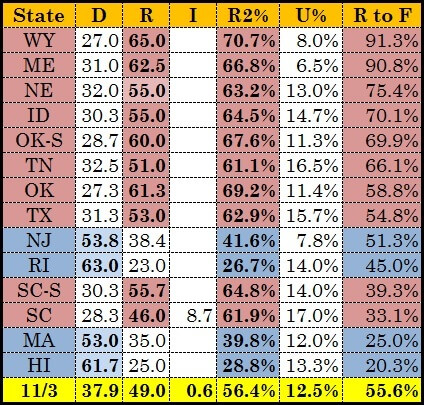

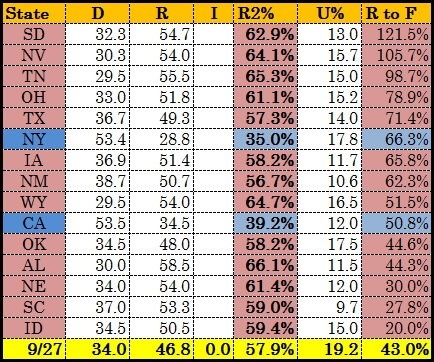

What if we take the “Breakers Report” chart from late September and re-run it to see what kind of break is needed to get the Republican to his or her actual, final vote share?

Virginia illustrates that late-breaking undecideds isn’t the whole story, as Warner lost support from where he was polling in late September. We also see here the terrible performance of Land and Wehby. And here as in some of the later charts, we see that states where the Democrats really put on a big turnout push in the ground game, like Colorado and Alaska, did yield them some more competitive results compared to the late September polls.

Whether due to polling error or voting-booth decisions, even the final polls didn’t fully capture the movement towards the GOP:

Here’s the Breakers Report charts for the Senate races compared to the final polls, divided into the two tiers I used in my final report:

Again, with the exception of Alaska, Colorado and South Carolina, we mostly see a break to the GOP in the races it won, and not in the blue-state holdouts (except Delaware, a state where the GOP failed to recruit a strong enough candidate to givee Chris Coons the race he deserved, and New Mexico, which had the same issue despite Allan Weh’s best efforts to make a fight of it). There was a lot of talk during the campaign about how the Democrats won the Colorado race in 2010 despite trailing in the polls on Election Day (then again, Republicans pulled the same trick in Colorado in 2002); what we see now is that the pollsters did a better job of correcting for that past error than they did in other states in weaning themselves off the 2012 models, but the Democrats’ Election Day ground game in Colorado is still strong enough that you’d worry if a Republican was only up a point there in the final polls. On the other hand, [mc_name name=’Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH)’ chamber=’senate’ mcid=’S001181′ ] managed to overperform her polls, after having underperformed them in 2002 and 2008.

The Governors

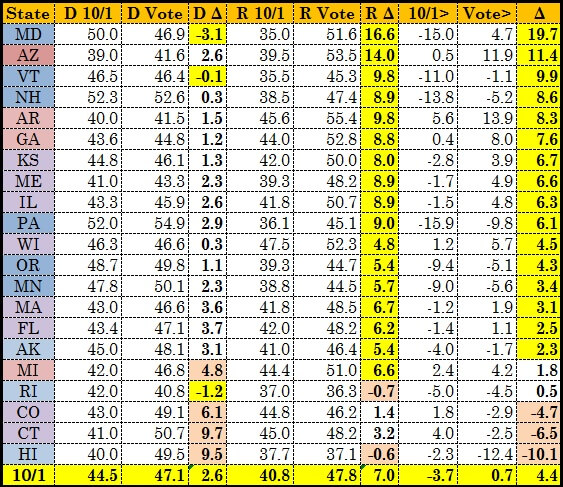

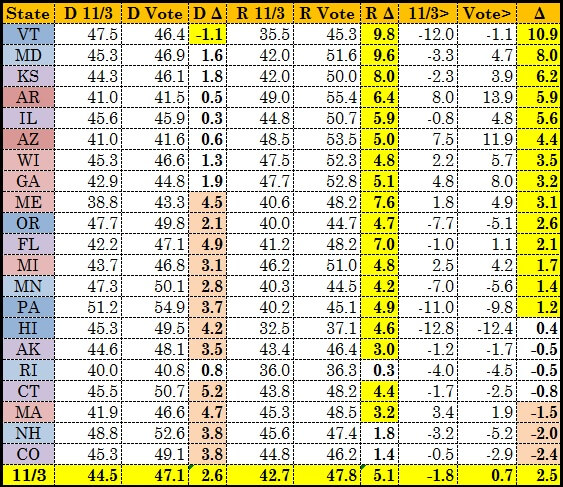

The bigger unknown, and one that neither I nor most anybody else subjected to as diligent study as was applied to the Senate races, was the 36 Governors races, about two-thirds of which were hotly contested. If we look at the trendline, they too show a strongly positive trend from October 1, with the exception of some races that went sideways in Colorado and Connecticut and the three-way races in Hawaii and Rhode Island:

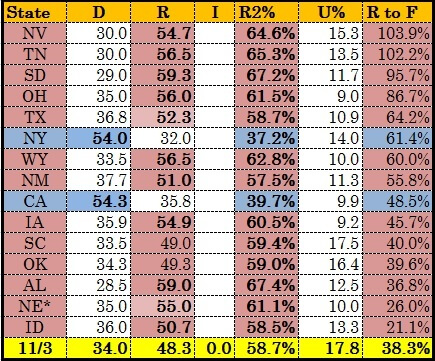

Arizona’s something of an anomaly because it had a late primary and at that point in the race there wasn’t much reliable polling yet. And the lower tier races, including some routs that turned into just epic landslides:

Here’s the Breakers Report for those, calculated from September 27 in the contested races (Robert Healey, the unfunded hippie running as the third party candidate in Rhode Island, wasn’t in the poll averages yet – he got 21% of the vote, as voters in one of the most Democratic states in the country vented their protests without backing the Republican):

and the less contested races:

As you can see, even in races like the New York Governor’s race there was a big late surge to Rob Astorino, reflective of how many races went more Republican in upstate and suburban New York than anybody had seen coming.

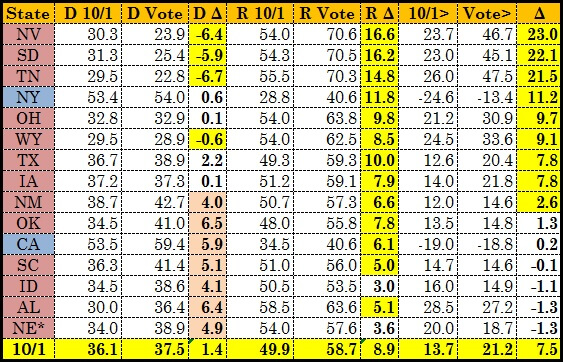

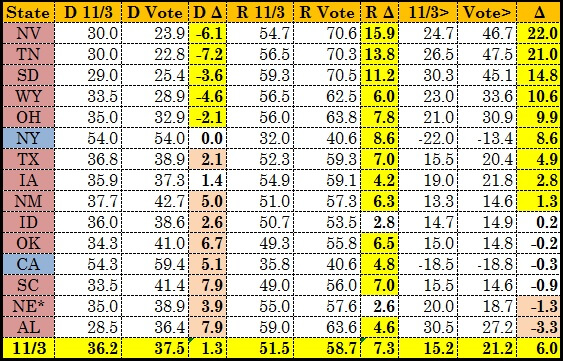

Republican candidates for Governor still did a good deal better with voters than the final polls indicated, some of them dramatically so:

and the second tier:

(It’s not surprising that the polling was weird in Nebraska, where YouGov was the only pollster in the field, but also that it wasn’t skewed in the way it was in other states – if you buy Silver’s theory that partisan skew derives in part from herding).

Then the final Breakers Report:

Maine’s break is so large it has to be partly attributable to polling error as far as modeling turnout. On the other hand, again: Alaska and Colorado. And I’ll get another day into some of the specific polls that went bad.

Does all of this mean that polls skewed to favor the Democrats, late breaks to the Republicans, and a steady march of the voters in the GOP direction are to be expected in future races? Of course not. Every election has its own dynamics, and some of those dynamics are cyclical between the parties. But we do know this: the fundamental trends of national politics that were observable in the 2014 presidential-approval and generic-ballot polls played out in a way similar to how they did in the 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2012 Senate races, while polls that bought into the repeatability of the Obama coalition without Obama on the ballot – and poll-analysis models that depended on the accuracy of those polls – were less successful in predicting the outcomes. Analysis of future elections should bear the historical trends in mind rather than assuming that it will always be different this time.