RS: How and Why Ronald Reagan Won

Fifty-one years ago today in Los Angeles, a 53-year-old political amateur, Ronald Reagan, gave a half-hour nationally-televised speech, “A Time For Choosing,” on behalf of Barry Goldwater’s campaign in the following week’s presidential election. 16 years later, Reagan would win 44 states and an almost double-digit popular vote margin of victory, kicking off the most successful and conservative Republican presidency in U.S. history, leading to a 49-state landslide in 1984 and the election of his Vice President for a “third Reagan term” in 1988, the only time in the past 70 years that a party has held the White House for three consecutive terms.

Given the extent to which Reagan’s legacy still dominates internal debates within the GOP and the conservative movement, it’s worth asking ourselves: What did he accomplish? How did he do it? And what can we learn from him today?

1. Reagan Moved The Country To The Right

From an ideological/political conservative perspective, the most important measurement of Reagan’s success is that he moved the country further Right than he found it. This is an important factor to bear in mind when Reagan’s legacy is misused both by those seeking unerring ideological purity and by those trying to capitalize on some of the ways in which Reagan took positions that would now be considered unacceptably moderate, liberal or compromising in today’s GOP. Reagan was a creature of his time and – to use Gandalf’s great line from the Lord of the Rings – “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” And so Reagan was, on the one hand, more interested in getting results than in demonstrating his 100% adherence to principle: he was fond of saying that “if you agree with me 80 percent of the time, you’re an 80 percent friend and not a 20 percent enemy” and “if I can get 70 or 80 percent of what it is I’m trying to get … I’ll take that and then continue to try to get the rest in the future.” On the other hand, if you told Reagan that the party had moved further to the right on some issues since 1988, he would undoubtedly be greatly pleased by the news. He himself moved to the right over time – from a New Deal Democrat in the 1940s, from the bill he signed early in his tenure as California Governor partly liberalizing the state’s abortion laws before Roe v Wade. And on other issues, as noted below, Reagan himself either left a lot of work unfinished (as on domestic discretionary spending) or made compromises (as on entitlements) as a concession to the political realities of his day.

Reagan unquestionably (though not alone) shifted the nation further to the right than he found it, in some ways temporarily and in other more lasting ways. Victory in the Cold War was the obvious headline – as late as 1979, there were voices throughout the West arguing that we could never defeat the Soviets and that Communism represented a viable alternative model to the American system, whereas today even an open socialist like Bernie Sanders cites the increasingly more free-market Scandanavian model. Reagan revolutionized the politics of taxes – in 1980, the top federal income tax rate was 70%, and married couples making $30,000 a year paid a top rate of 37%; at $35,000 they hit the 43% bracket. Taxpayers over $200,000 in income paid, on average, a total effective tax rate over 40%. These would be unthinkable tax rates today, when we argue over top marginal rates in the 35-39.6% band. Other long-term policy wins that shifted the conversation included ending the Fairness Doctrine, nominating the first explicit originalist to the Supreme Court (Antonin Scalia), breaking the air-traffic controllers union, finishing the (started under Carter) project of airline and trucking deregulation, and starting the free-trade processes that would yield dividends into the 1990s (he promised a NAFTA-like agreement in his 1979 speech announcing his candidacy). And Reagan’s victories laid the groundwork for the welfare reforms of Newt Gingrich (presaged in some of Reagan’s own policies as California Governor) and the law-enforcement revolution spearheaded by his U.S. Attorney in New York, Rudy Giuliani.

Or look at the electorate. We talk today about a general electorate dominated by Democrats, because the exit polls showed a D+7 electorate in 2008, D+6 in 2012 (that is, for example, 38% Democrats and 32% Republicans in 2012), and how this gave Barack Obama an unbeatable edge. But the electorate in 1976 and 1980 was D+15, with only 22% of voters in 1976 identifying themselves as Republicans. Yes, many more of the Democrats in those days were fairly conservative-leaning, not just in the South but in the Midwest, but these were still not people you could walk up to and say “I’m a conservative Republican” and have their vote (a March 1979 poll had Reagan trailing Carter 52-38). Even the South had gone heavily Democrat in 1976, with Carter carrying all but one state (Virginia) below the Mason-Dixon Line. Reagan in 1980 carried 27% of Democrats to Carter’s 67, and 56% of independents to Carter’s 31. And Reagan’s success changed the electorate’s view of his party – the electorate was D+3 by 1984, D+2 by 1988.

2. Reagan Delivered Tangible Results

Closely related to Reagan’s political and ideological success was that he did not just win inside-the-Beltway fights: he delivered real-world changes that voters could judge with their own eyes, which they did not need pundits to interpret for them. Inflation, which had been a dominant issue in the Ford and Carter years and which hit voters directly in the pocketbook, was decisively defeated by Reagan and Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker; it has never returned as a major issue. The gas lines of the 70s went away. Tax relief, including not just lower rates but an end to “bracket creep” (inflation pushing people into higher tax rates while their standard of living declined) was something people could see in their take-home pay. Unemployment, while stubborn, was in decline for years, the stock market boom roared, interest rates went down, and the economic growth rates from 1983-86 were out of this world. 15.1% of all U.S. workers made the minimum wage in 1980; by the mid-2000s, that number was down around 2%. The same dynamic was visible in foreign policy: problems that had been described as intractable under Carter suddenly started to give way, with an age of Soviet expansion and U.S. hostages giving way to the growth of U.S. power and the ultimate decline and collapse of the Soviet system.

Here’s how Reagan himself described his welfare reforms in California:

One lesson from this is that today’s conservatives still need to show people that their policies work. Another is not to focus too much on the abstract virtues of long-range fiscal policy to the detriment of things people can see and feel in their own lives. And listen: Reagan had always been against high taxes, but the 1978 California Prop 13 tax revolt helped convince Reagan to become a full-throated supporter of the Kemp-Roth supply-side tax reforms that would be the central defining feature of Reaganomics.

Reagan didn’t go around on the stump pledging fealty to conservative ideals, but rather explaining why his ideas would work in practice and why they were common-sense positions in line with what the voters already believed in, what had worked previously in practice, and what had long been traditional in America. And he wasn’t The Great Communicator because his speeches felt good, but because they said something concrete that people remembered. His pitch to voters was fundamentally a practical one: our ideas work.

3. Reagan Did His Homework and Knew What He Stood For

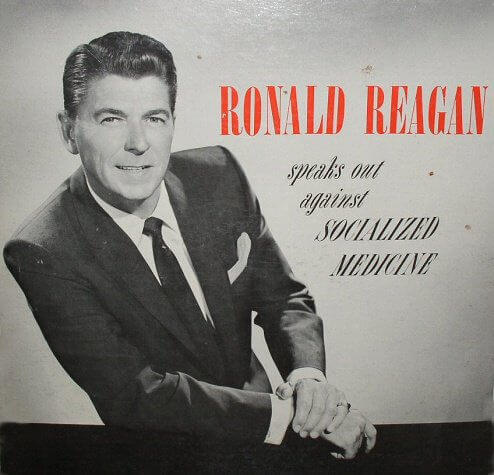

While Reagan’s pitch was practical, his grasp of public policy and institutional politics was well-grounded in years of study of both the theory of conservative philosophy (often bandied about in those days in publications like National Review and Human Events, of which Reagan was an avid reader) and the practical details of foreign policy and domestic political controversies (Reagan was also a voracious consumer of public-policy journals in the 50s, 60s & 70s). He was no Johnny-come-lately to the movement, like some of our more recent and nakedly opportunistic presidential candidates. His firm philosophical grounding enabled him to appraise potential compromises to see whether, in fact, conservatives were getting more than they were giving up – and his understanding of the playing field abroad and at home meant that he wasn’t learning on the job what the various agendas and procedural traps were.

I’d recommend five books to anyone trying to grasp Reagan – Thomas Evans’ The Education of Ronald Reagan, which covers the years in the 1950s and early 1960s when Reagan was evolving into a conservative and becoming more politically active; Reagan in His Own Hand, a collection of Reagan’s self-penned 1970s radio commentaries, which shows the breadth of his mastery of public policy at the time; Steven Hayward’s 2-part Age of Reagan series, the 1964-80 volume covering Reagan’s rise to power in the context of the political landscape of his day, and the 1981-89 volume covering his presidency; and finally Peggy Noonan’s What I Saw At The Revolution, her speechwriting memoir that captures the mood, the personalities, and the view of the “Reagan Revolution” seen from the eyes of an idealistic young speechwriter.

And knowing that the media and even the GOP’s own party elites would caricature him as an ignorant actor and an ideologue, Reagan put an enormous amount of effort into demonstrating his knowledgeability, and loved to pepper his speeches with statistics and concrete anecdotes. First of all, while he always had an eye on national issues (about a quarter of the 1964 speech was focused on foreign affairs), he didn’t dive directly into federal or national politics, but ran for and won two terms as Governor of the nation’s largest state, and still only won the White House on his second go-round. And his 1966 campaign focused on showing the voters that Reagan knew what he was talking about. From a 1966 profile:

from a retrospective on the campaign:

Reagan won over 3.7 million votes in 1966, enough votes to have won a majority even in the 2014 Governor’s race, after half a century of growth in California’s population. (In fact this was not Reagan’s first election, either; he’d been elected to two separate terms as president of the Screen Actors Guild). A few excerpts from Reagan in His Own Hand should give a sense of the kinds of things Reagan was talking about a decade later, before he launched his 1980 presidential bid.

On power politics in Africa:

On the Law of the Sea Treaty:

On telecom regulation:

On the SALT II Treaty:

4. Reagan Compromised and Picked His Battles

Reagan would never have been able to get the things done that he did – with the Democratic legislature in California, with a Democratic House in DC, even with the Soviet Union – if he didn’t know how to cut deals that gave the other guy something he wanted, a skill Reagan had learned in labor negotiations as both a union head and (with GE) negotiating for management. Thus, the reference to getting 70 or 80% of what he wanted – but thus also the recognition that Reagan could, for example, justify a tax hike here or there (as he did in 1982 and in some parts of the 1986 tax reform) because his overall record was unambiguously one of lowering taxes. But unlike some of today’s GOP leaders in DC, Reagan could pull this off because he had delivered enough of those tangible wins in the past to have earned some trust (Peggy Noonan described this attitude as “l’droit c’est moi” – Reagan so embodied the Right that it was impossible to convince voters he couldn’t be trusted). His reputation for making deals, but only those deals that benefitted him, let him usually negotiate from a position of strength: for example, he resisted calls for a summit with the Soviet Union until 1985, five years into his defense buildup and after he had clearly demonstrated that he was willing to take the heat for having no agreements with the Soviets at all. Yet while he used that leverage well, he also did ultimately sign a series of arms control agreements, agreements that made some real U.S. concessions in order to get a more broadly beneficial deal and keep a dynamic going that would be a winning one for us.

Reagan also trimmed his sails when needed on the campaign trail. In his 1976 campaign, he had talked about Social Security privatization and criticized Medicare and the Davis-Bacon Act; in 1980, he dropped any criticism of entitlements and won union support by pledging to retain Davis-Bacon. In office, he made only modest reforms to Davis-Bacon and signed a compromise bill on Social Security. He promised a woman on the Supreme Court, and delivered the decidedly moderate Sandra Day O’Connor. And even in his foreign policy, Reagan adhered to the first principle of U.S. foreign policy: triage that sets priorities rather than picks fights everywhere at once or else nowhere. Keeping his eye on the Cold War ball allowed him to get the maximum use of his political capital. At home, he accepted the loss of his pledge to balance the budget because it was more important to retain support for his defense buildup. And he knew when to lure his opponents into picking battles, too: while staging a symbolic and unsuccessful protest against the elevation of William Rehnquist to Chief Justice, the Senate let Scalia through unopposed.

5. Reagan Understood The Complementary Roles Of Party Establishments and Insurgents

Reagan’s famous “11th Commandment” – not speaking ill of another Republican – was a defensive tactic, designed to convince other 1966 contenders to debate him on the issues rather than attack him personally. After winning the nomination, he mended fences with the endorsement of moderate party elders like Dwight Eisenhower. Reagan was never averse to upsetting applecarts: he did, after all, run a primary challenge to an incumbent President in 1976. But when the nomination was cinched, after Reagan’s last-minute effort to mollify moderates with a liberal running mate (Pennsylvania Senator Richard Schweiker) Reagan publicly stood on the dais with Gerald Ford. Reagan wore down establishment opposition – by 1980, while the moderate establishment preferred George H.W. Bush, Reagan actually had more endorsements from elected officials (and picked Bush as his running mate). And he was unafraid to debate others on the Right – witness his vigorous 1978 debates with William F. Buckley over the Panama Canal Treaty.

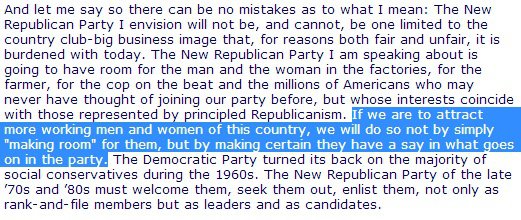

In short, Reagan saw the value of populist insurgencies, but also the practical value of translating them into a new governing structure side by side with the old bulls. Reagan’s CPAC speech in 1977 was explicit about the fact that bringing people along to join the party would have to mean being more open to listening to the new converts:

That was in line with his overall philosophy as set forth in his 1979 announcement speech:

I believe this nation hungers for a spiritual revival; hungers to once again see honor placed above political expediency; to see government once again the protector of our liberties, not the distributor of gifts and privilege. Government should uphold and not undermine those institutions which are custodians of the very values upon which civilization is founded—religion, education and, above all, family. Government cannot be clergyman, teacher and parent. It is our servant, beholden to us.

6. Reagan Understood The Role of Culture, Humor and Meeting The Voters Where They Are

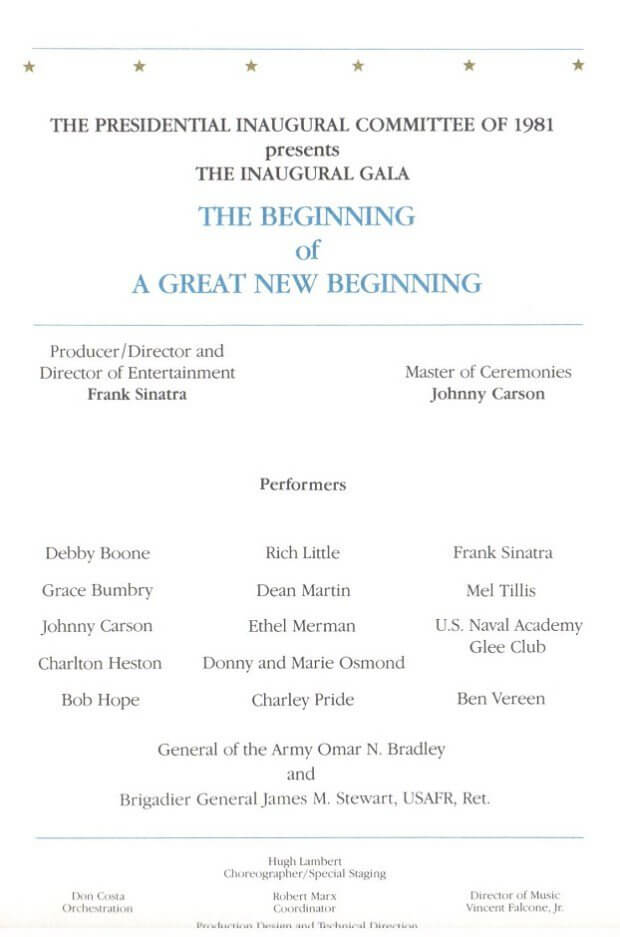

Reagan was not, as our party sometimes appears, distant, dour or perpetually angry. He was legendary for his humor (even when being wheeled into the operating room after being shot), unafraid to make jokes at his own expense but also expert at wielding mockery against the nation’s enemies. But his years in Hollywood also meant he still had friends in show business:

Reagan reached out to voters where he could find them, not always successfully but with a great overall record. He won young voters in 1984 by 19 points. He won 37% of Hispanics in 1980. He won self-described moderates, the only Republican candidate since 1976 to do so. He spent almost a full week in August 1980 pitching for black votes – speech to the Urban League, interviews with Ebony and Jet magazines, tour of the South Bronx. He touted to unions his background as a labor union president. In 1981, he got one Democratic Congressman to vote for his tax cut plan by calling in to him on a live radio show. Reagan argued for the GOP as a club anyone could join. And he loved to explain his conversion from a New Dealer and why he had become a Republican, rather than simply trying to convince people that he was – to pick a phrase – severely conservative.

7. Reagan Wasn’t Perfect

Finally, the challenge of adapting Reagan’s lessons to today includes recognizing that he, too, made mistakes. Some he came to see: the California abortion bill, his decision to send “peacekeeping” troops to Lebanon. Others were revealed by events: the 1986 immigration amnesty, the failed late-80s pursuit of “moderates” in the Iranian government, the Bob Jones tax fight. But this too should offer us perspective: even the best political leaders are not perfect. We should not be afraid to criticize our own leaders, nor expect of them perfect judgment. We must, instead, ask whether they have left our country, our party and our movement a better place than they found it.