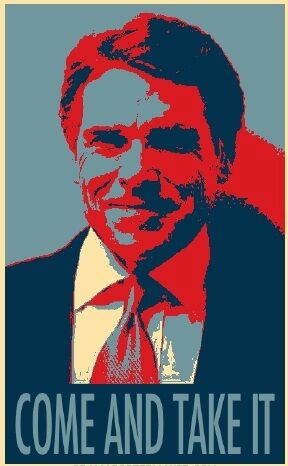

RS: The Vindication of Rick Perry

The Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas, the state’s highest criminal court, today threw out the entirety of the bogus criminal indictment against former Governor Rick Perry. The indictment was always a farce, and worse. Farce, because it suggested that Democrats would go much further than Republicans ever would to destroy a political opponent; worse, because it actively sought to criminalize good government by charging Perry with a crime for attempting to use his power of the purse to compel Democrats to get rid of a corrupt, alcoholic District Attorney who tried to abuse her office to get out of a drunk driving rap. The entire episode is a vivid reminder of why Rick Perry has been one of this nation’s most admirable leaders over the course of his career, and a man who deserved better in his runs at national office.

A lower appeals court had thrown out half of the indictment, but the Court of Criminal Appeals opinion disposes of the whole abusive case, and is worth reading if you’re into the kinds of separation of powers issues that Justice Scalia championed for years on the U.S. Supreme Court, and which the Texas courts take more seriously as a result of explicit language in the Texas Constitution:

The powers of the Government of the State of Texas shall be divided into three distinct departments, each of which shall be confided to a separate body of magistracy, to wit: Those which are Legislative to one; those which are Executive to another, and those which are Judicial to another; and no person, or collection of persons, being of one of these departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.

The court began by ruling that it would make an exception to its normal rules regarding “as applied” pretrial constitutional challenges to an indictment (i.e., arguments that the statute was unconsititutional only as it applies to this situation, not as to every possible set of facts) because of the importance of separation of powers to good government:

If a statute violates separation of powers by unconstitutionally infringing on a public official’s own power, then the mere prosecution of the public official is an undue infringement on his power. And given the disruptive effects of a criminal prosecution, pretrial resolution of this type of separation of powers claim is necessary to ensure that public officials can effectively perform their duties.

Turning to Count I of the indictment’s charge that Perry misused public money by vetoing the budget of the DA’s Public Integrity Unit in order to require it to show some public integrity of its own, the court emphasized that the public purposes to which a veto is put cannot be criminalized without destroying the veto power:

The Legislature cannot directly or indirectly limit the governor’s veto power. No law passed by the Legislature can constitutionally make the mere act of vetoing legislation a crime…the governor cannot by agreement, on his own or through legislation, limit his veto power in any manner that is not provided in the Texas Constitution…When the only act that is being prosecuted is a veto, then the prosecution itself violates separation of powers…A governor could be prosecuted for bribery if he accepted money, or agreed to accept money, in exchange for a promise to veto certain legislation, and a governor might be subject to prosecution for some other offense that involves a veto. But the illegal conduct is not the veto; it is the agreement to take money in exchange for the promise.

Count II charged Perry with “coercion of a public servant” for threatening the veto before he issued it, in order to pressure the DA to step down, as she should have. The lower appeals court had concluded that this statute applied in this manner would be massively overbroad in criminalizing completely legitimate politics:

The court of appeals recited a number of hypothetical situations offered by Governor Perry to illustrate the improper reach of the statute:

• A manager could not threaten to fire or demote a government employee for poor performance.

• A judge could not threaten to sanction an attorney for the State, to declare a mistrial if jurors did not avoid misconduct, or to deny warrants that failed to contain certain information.

• An inspector general could not threaten to investigate an agency’s financial dealings.

• A prosecutor could not threaten to bring charges against another public servant.

• A public university administrator could not threaten to withdraw funding from a professor’s research program.

• A public defender could not threaten to file a motion for suppression of evidence to secure a better plea bargain for his client.The court agreed that the statute would indeed criminalize these acts. The court also offered its own hypotheticals: that the statute would appear to criminalize a justice’s threat to write a dissenting opinion unless another justice’s draft majority opinion were changed, and the court’s clerk’s threat, when a brief is late, to dismiss a government entity’s appeal unless it corrects the deficiency.

A cynic would note that these examples cut rather too close to home for the judges.

The Court of Criminal Appeals agreed that the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution would be violated by the prosecutor’s broad view of what could be criminalized in a public official’s veto threats. The court noted that more specific situations of real misconduct like bribery were already covered by other statutes, and added its own list of real-world political give-and-take (which it linked to news reports of ordinary Texas politics) that would become crimes:

Th[e statute covers officials who] include[] the Governor, Attorney General, Comptroller, Secretary of State, Land Commissioner, tax-assessor collectors, and trial judges. Many threats that these public servants make as part of the normal functioning of government are criminalized:

• a threat by the governor to veto a bill unless it is amended,

• a threat by the governor to veto a bill unless a different bill he favors is also passed,

• a threat by the governor to use his veto power to wield “the budget hammer” over a state agency to force necessary improvements,

• a threat by the comptroller to refuse to certify the budget unless a budget shortfall is eliminated,

• a threat by the attorney general to file a lawsuit if a government official or entity proceeds with an undesired action or policy,

• a threat by a public defender to file, proceed with, or appeal a ruling on a motion to suppress unless a favorable plea agreement is reached,

• A threat by a trial judge to quash an indictment unless it is amended.Of these, the only example involving anything unusual is the one in which the comptroller actually followed through with her threat not to certify the budget. At least some of these examples, involving the governor and the attorney general, involve logrolling, part of “the ‘usual course of business’ in politics.”

Another indication of the pervasive application that the statute has to protected expression is that the last example we listed above occurred in this very case. Concluding that quashing Count II would be premature, the trial court ordered the State to amend Count II of Governor Perry’s indictment. But a trial court has no authority to order the State to amend an indictment; the State has the right to stand on its indictment and appeal any dismissal that might result from refusing to amend. The trial court’s order that the State amend the indictment was, in practical terms, a threat to quash Count II if it were not amended. And the trial court’s exact words are of no moment because the statute refers to a threat “however communicated.”

The regular and frequent violation of the statute by conduct that is protected by the First Amendment suggests that the statute is substantially overbroad.

In theory, because the dismissal of Count II was on federal Constitutional grounds, the prosecutor could appeal that ruling to the 8-member U.S. Supreme Court, but it appears that this is the end of the line. Rick Perry stood his ground for honest government and was branded a criminal for doing so, long enough to help hobble his 2016 Presidential campaign. Everyone involved in that effort should be ashamed of themselves. But tonight, Governor Perry can hold his head high, as he has been completely vindicated.