Where were you when Cal Ripken broke the consecutive games record? You don’t remember, do you? Did you even watch the game? I didn’t. Sure, it was interesting at the time, but a moment you will remember forever? If you’re keeping score at home, Major League Baseball’s fan voting produced this Top Ten List:

The Top 10 Most Memorable Moments (as voted by fans):

1. 1995 – Cal Ripken breaks Lou Gehrig’s streak with his 2,131st consecutive game.

2. 1974 – Hank Aaron breaks Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record.

3. 1947 – Jackie Robinson becomes the first African-American Major Leaguer.

4. 1998 – Mark McGwire & Sammy Sosa surpass Roger Maris’ single-season home run record.

5. 1939 – Lou Gehrig retires with his “luckiest man” farewell speech.

6. 1985 – Pete Rose passes Ty Cobb as the all-time hits leader.

7. 1941 – Ted Williams is the last man to post a .400 average.

8. 1941 – Joe DiMaggio hits in 56 straight games.

9. 1988 – Kirk Gibson’s pinch-hit homer sends LA on its way to a World Series upset.

10. 1991 – Nolan Ryan pitches his seventh career no-hitter.

Here’s the complete 30-moment ballot, and ESPN Page 2’s list of moments they left entirely off the list.

The two lists, totaling 40 ‘moments,’ present an inviting target, although

each does bear the marks of careful selection of more of the moments than not. They left off the Merkle incident in 1908, when the pennant race turned on rookie Fred Merkle’s failure to touch second base on a game-winning hit (he was on first). Many other pre-1930 moments get ‘dissed’ here – like the stunning conclusions to the 1912 and 1924 World Serieses, the incredible finish to the 1908 AL pennant race, the Black Sox fixing the World Series, and the Yankees crushing the Pirates in the 1927 World Series – and given how few people still remember them, maybe that’s understandable. I might also quarrel that Maury Wills’ stolen base record was more memorable than Rickey’s, and that I, at least, remember Nolan Ryan’s fifth no-hitter as the milestone, not the seventh. After the furor over Roberto Clemente being left off the All-Century team, it’s also understandable that MLB picked Clemente’s last hit, Ichiro’s MVP award, and Satchel Paige’s Hall of Fame induction to satisfy as many constituencies as might be offended. The latter was far from a fitting tribute to Paige, but since many of his best moments are closer in memory to Paul Bunyan stories than documented facts, it’ll have to do. For each of the three, it’s really an inclusion more of the man than the moment, and they are certainly all worthy of a certain share of the game’s honors.

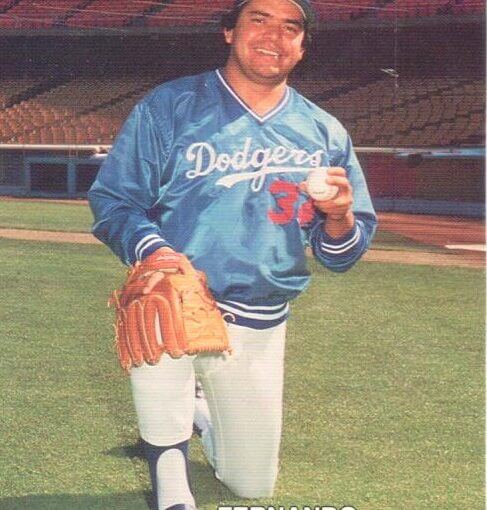

Anyway, the inclusion of Clemente and Ichiro, coming alongside the late-season phenomenon of Francisco Rodriguez, brought to mind another of baseball’s truly phenomenal runs, and one that is maybe not as well-remembered as I would have thought at the time: Fernandomania!

Look back at the statistics from Fernando Valenzuela’s rookie season, when he won both the Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards and was fifth in the MVP voting, and you’ll see a very good pitcher in a strike-shortened season; but if you’re not old enough to remember 1981, you may wonder what the fuss was about. In 25 starts, Valenzuela went 13-7 with a 2.48 ERA, good for second in the league in wins and seventh in ERA, although he did lead the league in innings (192.1) and strikeouts (180).

But one number hints at the real story: 8 complete-game shutouts. In 25 starts.

In 1980, Fernando, then “19” years old (my mom thought he was 40 when she first saw him), came up at the end of a season when the Dodgers were in an insanely tight pennant race, one that ended with a 1-game playoff, which the Dodgers lost to the Astros. He made his debut on September 15, and pitched so well that Tommy Lasorda used him 10 times in relief down the stretch, 6 of them for 2 innings or more. Over the season’s last nine games, including the playoff, Fernando pitched 6 times, throwing 10 scoreless innings, finishing four games – including two wins and a save – striking out 9 while allowing four hits. He pitched 2 innings in the last scheduled game of the season against the Astros (the Dodgers won to force the playoff, with Don Sutton making one of just 4 relief appearances he would make between 1969 and 1988 to get the save), and 2 more in the playoff. The final numbers: 10 games, 0.00 ERA, 17.2 IP, 8 hits, 5 walks, 16 K. 16 straight scoreless innings after allowing 2 unearned runs in his debut.

In 1981, the Dodgers decided to put the Mexican phenom in the rotation and let Sutton and his 230 career victories walk as a free agent. To the Astros, no less. Lasorda turned up the heat and the hype even further by naming the rookie to start Opening Day at home against Houston and Joe Neikro.

He threw a 5-hit shutout, and won 2-0. In his second start, Fernando tossed another complete game victory at Candlestick, striking out 10 Giants and allowing just a run on 4 hits. In his third start, another 2-0 victory, a 5-hit, no-walk, 10-K blanking of the Padres in San Diego. Oh, and he went 2-for-4 at the plate. Start #4 was on to the Astrodome to face the defending division champs again; Fernando went the distance on a 1-0 victory, striking out 11, and added two hits and the game’s only RBI for good measure. Start #5 was back home against the Giants, and another complete game shutout; Fernando also had 3 hits and drove in the go-ahead run. In Start #6, in Montreal, Fernando went 9 innings again, allowing one run, and left with the game tied 1-1; the Dodgers scored 5 in the tenth for another victory. I first saw him that season in Start #7, matched up at Shea against Mike Scott, who pitched what looked (until 1986) like the best game he’d ever throw; the Dodgers got just a single run off Scott, but Fernando went the distance yet again, winning 1-0. Here’s his record at that point:

1981: 7-0, 0.29 ERA, 7 starts, 7 CG, 5 shutouts, 63 IP, 40 H, 2 R, 2 ER, 0 HR, 16 BB, 61 K. On the season, he was also hitting .318.

Career: 9-0, 0.22 ERA, 80.2 IP, 48 H, 4 R, 2 ER, 0 HR, 21 BB, 77 K.

He had already posted scoreless inning streaks of 35.2 innings AND 32.2 innings – in a career spanning just over 80 innings of work. He had beaten mostly good teams, and he had come out ahead in an exceptional run of close, low-scoring games. He had pitched in pennant race pressure, and he had taken the place of a Hall of Famer on Opening Day. (You can check my source, the game-by-game breakdown of his season at Retrosheet).

In his next start, Fernando went the distance on a 3-hitter for a 3-2 nail-biter against the then-mighty Expos, scattering a pair of solo homers, the first two of his career, to go 8-0. This raised the Dodgers’ record to 23-9 and their division lead to 5.5 games; by Fernando’s next start, they were 26-9, and only the Big Red Machine, in its last hurrah, was within 7 games of them.

The effect of all this was electrifying. Fernando was everywhere, and between the shutouts and the hitting and his eccentric, roll-the-eyes-to-heaven delivery, he was being compared to a cross between Sandy Koufax, Babe Ruth and Mark Fidrych. His first home start after the three straight victories on the road drew more than 49,000 fans to a Monday night game at Dodger Stadium, followed by a crowd of over 46,000 in Montreal (granted, between 1979 and 1983, the Expos were never lower than fourth in the league in attendance), almost 40,000 for a Friday night game against a dismal Mets team, 53,000 for a Thursday night game in LA, and 52,000 for a Monday night game in LA against the Phillies. Not all of his starts were packed, and attendance would be off later in the year following the strike, but there was no question that, especially among LA’s huge Mexican-American population, Fernando was a big draw.

You may think of Clemente and Juan Marichal as the trailblazers for Latin American ballplayers – you could even go back as far as Dolf Luque, the “Pride of Havana,” in the 1920s – but those guys blazed it with little company. It was Fernando more than anybody who really represented the turning of the tide to Latin American players as commonplace in the game; more than that, it was the marketing potential tapped by Fernando that helped teams overcome the fear that Latino players wouldn’t be popular.

Valenzuela cooled off eventually, with some rough outings in late May and early June, and by the end of May his batting average, as high as .360 at one point, fell below .300. He would have some more spectacular successes late in the season, have several more great years including a 21-win season in 1986, and earn a deserved reputation as a great big-game pitcher with a 5-1 record and 1.98 ERA in six postseason serieses, including three wins en route to the Dodgers’ 1981 World Championship. By age ’25,’ he had won 99 major league games; eventually, though, he broke down from severe overuse by Tommy Lasorda, which you can see in the 1981 records as well as the stretch in late 1987 when Lasorda left a struggling Valenzuela on the mound to throw 150 pitches in three consecutive starts, followed by a complete game, followed by a 10-inning complete game. Last I heard, he’s still pitching somewhere in Mexico; who knows if he’ll be back again someday for one of the abortive comebacks he’s pursued for the last 14 years. We probably never will know how old he actually is.

But all that is epilogue. If you want a “moment” when a new arrival turned the baseball world on its ear — well, there’s Jackie Robinson, and there’s

everybody else. But aside from Robinson, even the likes of Ichiro, Fred

Lynn, Karl Spooner and Harry Krause paled in comparison to Fernandomania.

_________________________________

FUN FACT: Fernando has hardly been the only Latin American pitcher to star in the postseason. Before Livan Hernandez’ shellacking in Game 3 of the Series, ten Cuban-born pitchers had appeared in the postseason, with a combined record of 23-9 with a 2.70 ERA in 296.1 IP spread over 38 postseason serieses. Only two Cuban-born pitchers had a losing record in the postseason: Camilo Pascual and Diego Segui, each 0-1. The bulk of the pitching has been done by Orlando Hernandez (9-3, 2.51), Mike Cuellar (4-4, 2.85), Livan (6-0, 2.84 through the 2002 NLCS) and Luis Tiant (3-0, 2.86), with honorable mention to Luque (1-0, 9.1 scoreless IP).