RealClearPolitics election analyst Sean Trende has come under coordinated red-hot rhetorical fire from the Left for his thesis that one of the major causes of Mitt Romney’s loss in 2012 was that a disproportionate number of white voters – mostly downscale whites outside the South – stayed home. Much of the criticism of Trende’s thesis is based on deliberately misreading his policy prescriptions – but it’s also based on a simpler failure to grasp the basic math behind his calculations. Like any exercise in reading exit polls and census data, Trende’s assumptions (which he lays out explicitly) can be critiqued by people who are serious about understanding the issue; there are no definitive answers in this area other than final vote counts. But the vehemence directed at Trende’s number-crunching suggests a Democratic establishment that fears honest debate intruding in its narrative of an inevitable, permanent Democratic majority built on a permanently racially polarized electorate.

Trende’s Theses

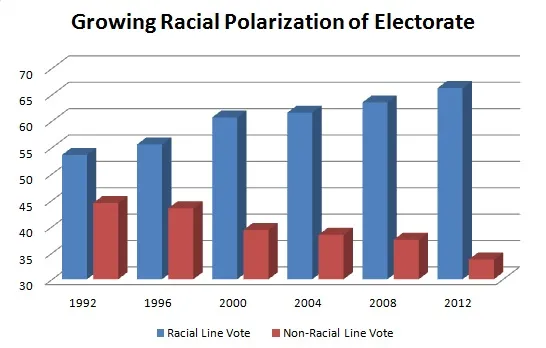

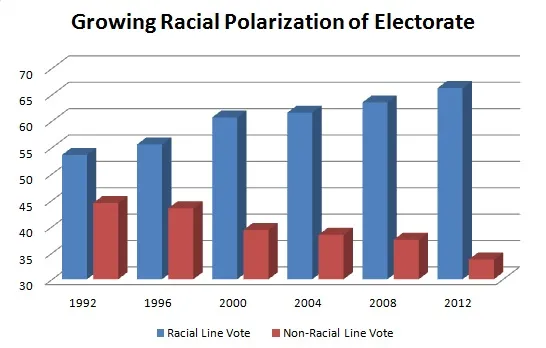

Given the intense and growing racial polarization of the Obama-era electorate, it is sadly necessary to look at the race of voters to make sense of what happened in 2012 and what it says about the two parties’ coalitions going forward; on this, analysts on all sides agree. Indeed, those who argue for a long-term Democratic majority do so primarily on the basis of maintenance of current levels of racial division. It is also agreed among all analysts that turnout was down in 2012 from 2008; the raw numbers show that about 2.2 million fewer people voted, while the population grew. The issue is how to measure the rates of turnout among each racial group.

Who The Missing Voters Were

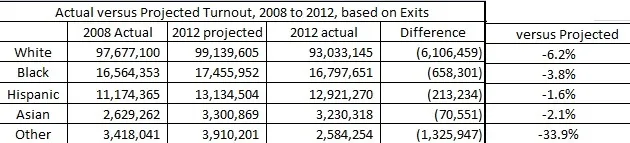

Trende’s original thesis was based on the initial exit polls released immediately after the election as compared to Census Bureau population estimates, and developed in a four part series beginning last month. Naturally, given the nature of the data sets involved, his numbers changed as more precise sources of data became available. He conducted a simple five-step exercise:

1. Look at voter turnout – total and by race – in the 2008 election;

2. Look at Census data to determine the growth of eligible voters in each racial category;

3. Project what the 2012 electorate would have looked like if each category turned out at the same rates as in 2008, but adjusted for the 2012 population;

4. Look at voter turnout – total and by race – in the 2012 election;

5. Compare Step 3 to Step 4 to determine how each group’s rates of turnout changed from 2008 to 2012.

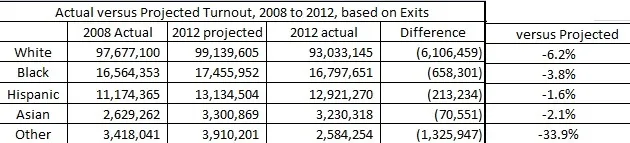

This is not a controversial methodology; total population growth and total election turnout are hard data, and the only real issues are which of various Census reports you use to compute population growth by racial category, and which of various election sources you use to compute turnout by racial group. With a little cutting and pasting to combine his two charts, here is what Trende’s June analysis concluded:

In other words, compared to 2008 levels of turnout, white voter turnout was down far more than non-white voter turnout (6.2% vs 3.8% for black voters and 1.6% for Hispanic voters), and there were approximately 6 million “missing white voters,” as compared to about 871,000 black and Hispanic voters. Trende also finds about 1.3 million missing “other” voters (“other” being mainly mixed-race voters, as well as Native American, South Asian, and other groups – not necessarily a bloc as heavily Democratic as black or Hispanic voters). The “other” group is a statistically significant part of the analysis, but, as Trende’s later analysis shows, that last figure may be an anomaly due largely to mathematical rounding issues, without which the number of “missing” non-white voters in total drops in half when you use later, more accurate data – more on that below.

There is one error in Trende’s computation, which brings his total short of the 129.2 million votes cast in 2012, and that’s Asian voters (who have broken heavily Democratic in recent elections after being a GOP voting bloc in the Reagan-HW Bush years). Trende finds about 70,000 Asian voters missing, when in fact Asian turnout was up enough that he should be showing about 575,000 extra Asian voters (I contacted Trende and he confirmed this). Asian voters are an oft-overlooked and growing piece of the puzzle, and they still turn out in very, very low numbers compared to their (still-small) share of the US population, but reaching out to them is an important consideration going forward. In any event, when you adjust for the proper counting of Asian voters, you find that it actually strengthens Trende’s thesis that white voter turnout was down relative to turnout of the major non-white voting blocs.

Where The Missing Voters Were

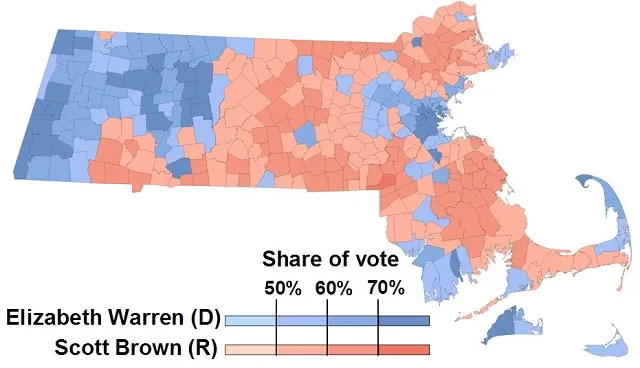

Trende also produced a map showing where the missing voters were most likely to be found, although the map can’t break them out by race; the areas in blue on the map represent the biggest drops in turnout, red represents growth in turnout compared to population growth.

As you can see from the map, a good number of the “missing” voters were in uncontested states like New York and Oklahoma where they would not have made a difference. And the big chunks of deep blue in New Mexico, Oklahoma and South Dakota (as well as the heavy dropoff in turnout in Alaska, not shown on the map) are consistent with a dramatic decline in Native American voter turnout.

But a significant number of others were in Pennsylvania (Obama by 309,840 votes out of 5.75 million cast), Ohio (Obama by 166,272 votes out of 5.59 million cast), Michigan (Obama by 449,313 votes out of 4.74 million cast), and Minnesota (Obama by 225,942 votes out of 2.94 million cast). This is consistent with Trende’s conclusion that – while these voters were not, in and of themselves, the cause of Romney’s loss – they were a contributing factor large enough to consider, and one that may loom even larger in a closer future contest between a better Republican candidate and a Democrat who has less visceral appeal to non-white voters. (The lower turnout throughout the Northeast also surely reflects the influence of Hurricane Sandy).

The White-Voter Path To GOP Victory

Later in his series, Trende moved on to a second thesis: that it’s possible – not likely, but possible – that depending how turnout develops (eg, if African-American turnout and voting patterns revert to pre-Obama levels), that the GOP could start winning national elections on the basis of winning a growing share of the white vote without eroding the Democrats’ hold on non-white voters. As Trende notes, while this scenario requires some leaps from where we stand today, white voters have been trending gradually more Republican:

Democrats liked to mock the GOP as the “Party of White People” after the 2012 elections. But from a purely electoral perspective, that’s not a terrible thing to be. Even with present population projections, there are likely to be a lot of non-Hispanic whites in this country for a very long time. Relatively slight changes among their voting habits can forestall massive changes among the non-white population for a very long while. The very white baby boom generation is just hitting retirement age, and younger whites, while unsurprisingly more Democratic than the baby boomers (who, you may recall, supported George McGovern), still voted for Romney overall.

Nowhere does Trende argue for the GOP to turn up its nose at Hispanic outreach, or counsel a harder line on immigration; rather, he argues simply that there are enough different variables that it’s unwise to write off the GOP just yet on the basis of mathematical and demographic determinism, even if the GOP does defeat the current iteration of “comprehensive immigration reform.” There is more than one way to build a winning electoral coalition.

Trende’s Critics

The main salvo against Trende can be found in a belligerent ThinkProgress blog post by Ruy Teixeira and Alan Abramowitz entitled, “No, Republicans, ‘Missing’ White Voters Won’t Save You.” Stripping away the rhetorical overkill (“GOP phone home! Your missing white voters have been found, and it turns out they weren’t really missing”), the main point of contention is that Teixeira and Abramowitz simply reject the notion that turnout was down at differential rates:

Trende was using an estimate of around 2.7 million additional eligible whites between 2008 and 2012. That’s wrong: Census data show an increase of only 1.5 million white eligibles….[U]sing Census data on eligible voters plus exit poll data on shares of votes by race, we calculate that turnout went down by about equal amounts among white and minority voters (3.4 and 3.2 percentage points, respectively).

This attack on Trende was predictably amplified by Paul Krugman, who doesn’t seem to have even read Trende’s essays, calling them a “Whiter Shade of Fail”; Krugman concludes on the basis of reading the ThinkProgress blog post that “the missing-white-voter story is a myth.” (Josh Marshall takes a similar line).

But careful reading is your friend. And a careful reading shows why Teixeira and Abramowitz are long on vitriol – because they are short on trustworthy data.

The immediate problem here is that Teixeira and Abramowitz don’t show their work to explain how they come up with these percentages, so a certain amount of deductive detective work is required to figure out what they did (not making your computations transparent is generally not a sign of confidence in your data). From the links in their post, it appears that the main issue is that they and Trende are using different Census Bureau reports for their data. Also, critically, Teixeira and Abramowitz don’t break out turnout among the component elements of “non-white” voters, who they treat as a monolithic mass.

The CPS Bait and Switch

As Trende observes, Teixeira and Abramowitz “look at a different data set — the CPS [Current Population Survey] data,” a monthly survey in which people self-report employment data and (after the election) self-reported voting participation. Trende, by contrast, used Census Bureau population estimates derived from the actual 2010 Census.

If you take it at face value, however, the CPS survey has a serious flaw that should be obvious even to a Nobel Prize winner:

[T]he CPS data conclude that there were 1.4 million more Hispanics who voted in 2012 than in 2008, 547,000 more Asians, 1.7 million more blacks, and 2 million fewer whites. That works out to a total of 1.8 million more votes cast in 2012 than 2008, according to the CPS survey.

But if there is one thing that we absolutely know about 2012, beyond any reasonable doubt, it is that turnout actually dropped from 2008….So, the CPS data say that there were around 4 million more votes cast in 2012 than was actually the case.

In short: the CPS turnout figures cannot possibly be correct. It’s like a preseason baseball prediction where the whole league is over .500. It’s mathematically impossible. Now, it’s certainly possible that CPS is wrong proportionally – that is, that it overreported the turnout of all groups equally. It’s also certainly possible that it’s not proportionate. But there’s no way from looking at CPS alone to know, so relying on it as an authoritative source without caveat or explanation is a very questionable choice.

Teixeira and Abramowitz stake their whole argument on the CPS – but then they use it selectively. As noted above, the actual turnout figures produced by CPS support the idea that white turnout was down in absolute terms, while black, Hispanic and Asian turnout was up. If they broke these groups out individually, as they appear in the CPS data itself, that would destroy their entire argument that turnout was down equally across all groups. So they do two things to cover their tracks. One is to clump these groups together with “other” non-whites; but as Trende notes, “the large mass of missing ‘other’ voters is probably a rounding issue. This isn’t a minor point; those voters represent 60 percent of all the non-whites that Teixeira and Abramowitz are discussing.”

Second, as Trende demonstrates, Teixeira and Abramowitz are only able to use the CPS data to their advantage by mixing and matching it with other sources (specifically, exit polls) – if you use only the CPS, “the CPS data actually show a larger decline in the white vote than do the exit polls.” (Trende, because he’s using non-election-related Census data, has to use the exit polls for his turnout figures – but if Teixeira and Abramowitz think CPS is the more reliable source, why do they avoid using it to compute turnout?)

There is no perfect answer to these questions. The Census is the best possible population figure, but the interstitial estimates involve some inherent guesswork. Exit polls may be biased in who answers them, and the CPS is obviously biased to over-report voting and may be biased in who over-reports; we can’t know. (One difference being that exit poll respondents don’t know who won the election when they respond; CPS respondents do, so there may be a possible bias towards overreporting by non-voting supporters of the winner. But that’s speculation.) What we do know is that Trende has put his methodological choices on the table and they are reasonable ones; Teixeira and Abramowitz have not, nor offered any defense for their methods, nor explained how they can square their theory of perfectly proportional decline in turnout across groups with the fact that the very source they use shows the opposite. Under those circumstances, it’s not hard to decide who to trust.

The Wider Universe of Missing Voters

For all the heat over Trende’s computations, it should not be forgotten that the “missing white voters” are only the difference in turnout patterns between 2008 and 2012 – both elections in which uninspiring and poorly-organized GOP campaigns faced off against Barack Obama (a uniquely inspiring figure to non-white voters due to his status as the first non-white President), and the first of which – the baseline – already involved a uniquely bad political environment for Republicans. In fact, voter turnout is a volatile variable that changes from one election to another; while it can be useful to perform an exercise like Trende’s, it requires a serious failure of imagination to regard the 2008 and 2012 turnout environments as the outer boundaries of potential voter turnout.

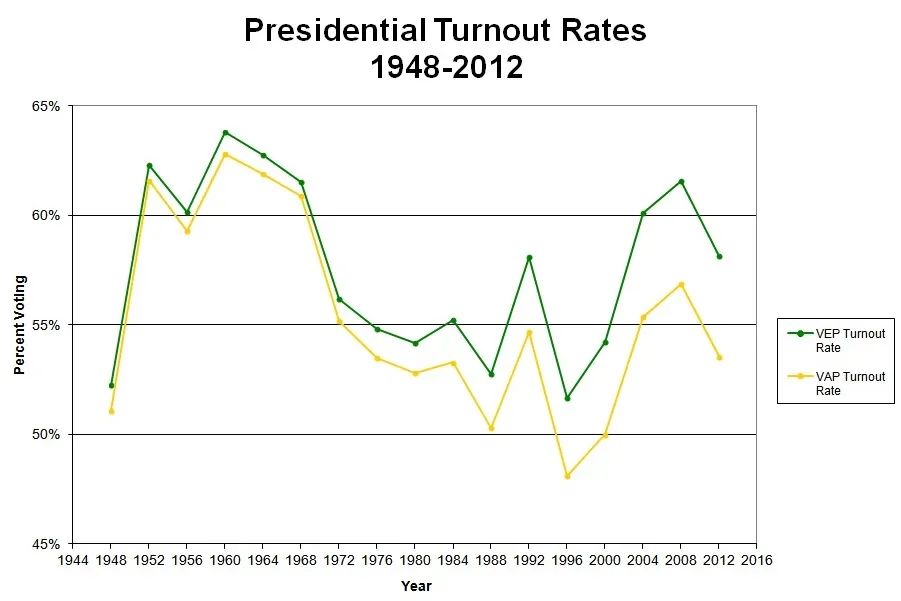

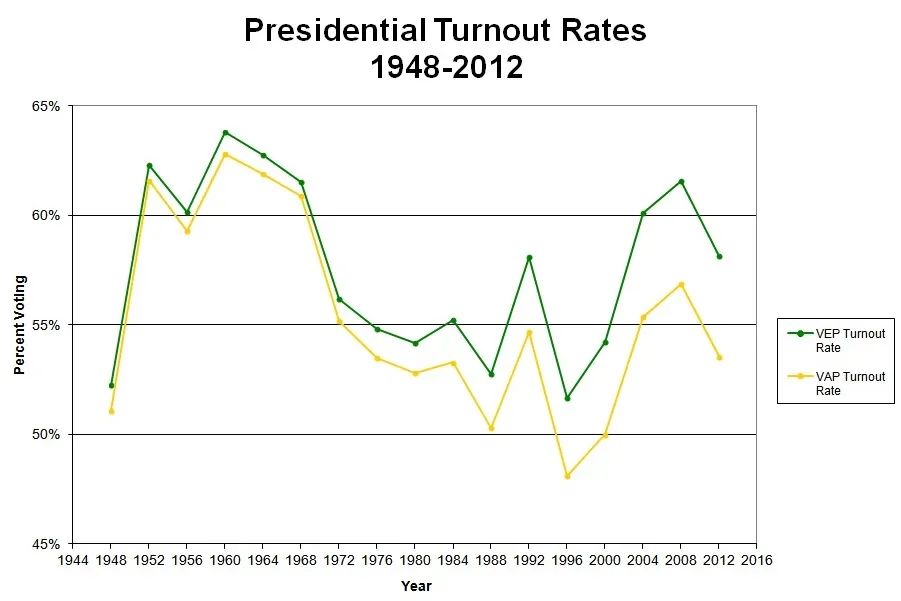

How many voters are “missing” depends very much what your baseline is – a baseline that never stops moving. It’s debatable exactly how many eligible voters there are at any given time (different sources use different measurements) but consider that Michael McDonald of George Mason University (on whom Teixeira and Abramowitz rely) figures a “voting eligible population” of 221,925,820 in 2012 – which means that compared to the entire universe of eligible voters, there weren’t six or eight million missing voters, there were 92.7 million missing voters, 40% more than the total that voted for Obama. On the other hand, McDonald calculates that, while 58.2% of eligible voters voted in 2012, only 51.7% voted in 1996 when Bill Clinton ran for re-election. If you take McDonald’s figures and use 1996, the last election with an incumbent Democrat on the ballot two years after a GOP rout in the Congressional midterms, as your baseline, suddenly you’re not talking about missing voters at all – you’re asking where 8.4 million extra voters came from.

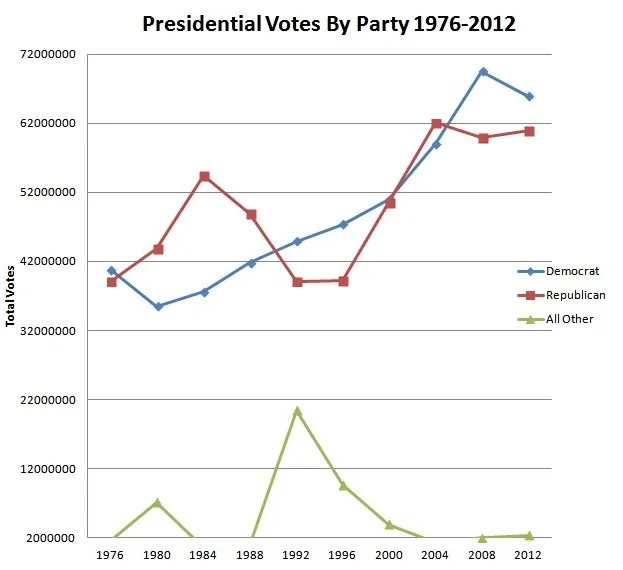

I do not, of course, mean to suggest that there were 92 million voters that either campaign could reasonably have expected to turn out. My point is, the dropoff of some 6 million eligible white voters and 1.6 million eligible non-white voters as compared to the 2008 baseline is just one segment of a much broader universe of eligible non-voters, some of whom will doubtless be turned out by the winning presidential campaign in 2016 or 2020, just as some of the folks who turned out for Obama, Romney or McCain will surely drop out of the process in the next two elections even if they remain eligible voters. Turnout as a whole can be volatile over time, as McDonald’s estimates show:

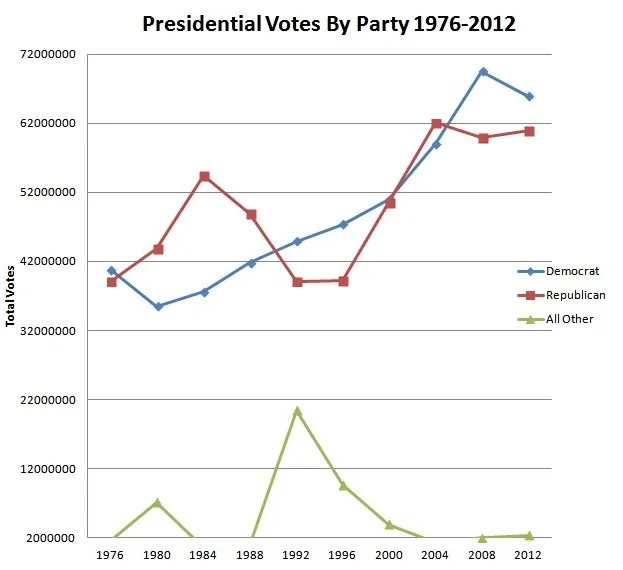

Turnout rates dropped as more previously ineligible voters entered the system, particularly after the voting age was reduced; it spiked in 1992 when Ross Perot’s campaign offered an outlet to voters unhappy with both parties, and again in 2004 and 2008 as the Bush and Obama campaigns found distinctly different paths to bring previously disaffected voters to the polls. The increasing volatility of turnout rates in recent years suggests that improvements in technology, combined with changes in voting practices (e.g., early voting) may be improving campaigns’ ability to locate new voters. And there’s a second, equally important piece of the puzzle that I frequently stress: the two parties’ bases, turnout methods and reasons for appealing to voters are asymmetrical. Look at this chart of the vote totals of the Democratic and Republican tickets in presidential races between 1976 and 2012:

The Democrat vote grew steadily year to year throughout this period, consistent with the view (implicit in all of Teixeira’s analyses and those who follow a similar demographics-are-everything approach) that the Democrats are mainly a collection of interest groups that grow with the populations they represent. The Republican vote, by contrast, was much more volatile (and susceptible to being drawn off by dissenters like Perot), reflecting the fact that Republicans are a more ideological party and therefore more dependent on the issue environment (particularly the presence of national security as a major issue) and the quality of the party’s candidate and platform to draw votes. Candidates and campaigns still matter, and matter more to Republicans. It’s entirely plausible to think the GOP will run better candidates and better campaigns in the future – that the McCain and Romney campaigns were not the best of all possible Republican campaigns.

Specifically, we are not so far removed from George W. Bush and his Karl Rove-led political operation figuring out how to increase the GOP vote from 39 million voters in 1992 and 1996 to 50 million in 2000 and 62 million in 2004, a feat that astounded liberal observers at the time and upended conventional wisdom that the GOP could only succeed in a low-turnout environment. The 2004 election came after Ruy Teixeira and John Judis had published their “Emerging Democratic Majority” book in 2002, and Teixeira spent the 2004 election arguing so vociferously that the polls were overestimating Republican turnout that Mickey Kaus acidly remarked the day after the election “Bush 51, Kerry 48: Pollster Ruy Teixeira demands that these raw numbers be weighted to reflect party I.D.!”

Teixeira wasn’t the first or last election analyst to assume that dramatic changes in the turnout environment were implausible; many observers on the right, myself and Trende included, spent a good deal of 2012 questioning how Obama could recreate the dramatic shift away from 2004’s turnout that we saw in 2008. The point here is the danger of assuming that present trends will continue unabated forever.

In short, we’re discussing the current margins – of the 92.7 million eligible voters who passed on the Obama-Romney contest, around 9% of those would have shown up at 2008 levels of turnout; of the 129.2 million who did vote, around 6% of those would have stayed home at 1996 levels of turnout. But until we run the next election, we don’t know how far each side can push those margins, or with which populations of eligible but not certain voters. The history of American politics suggests that we have not seen the last new development that will surprise observers of the political scene.

Ruy Teixeira’s Methods Seem Familiar

Reading through Texiera’s flailing assault on Trende, I felt a strange sense of deja vu – because I had read this before, in Teixeira’s review of Jonathan Last’s excellent book What to Expect When No One’s Expecting. And as with his dismissal of Trende, Teixeira’s review was greeted by the usual head-nodders on the Left as an excuse not to deal with Last’s arguments but rather dismiss them out of hand.

Last’s book develops his argument that birth rates in the United States and around the world are falling to a point that threatens a declining population, that many changes in society, economics and government can flow from such a demographic shift, and that a lot of these could be very, very bad. Last’s book notes that Hispanics (particularly recent arrivals to the U.S.) have been the only major group having enough children to keep the United States from falling below “replacement level” birthrates, but that trends among Hispanics suggest that they may also fall back towards the rest of the U.S. population over time. Finally, he argues that, while immigration has helped the U.S. stave off the more dire declines in population faced by countries like Japan, Russia and Southern Europe, there are downsides to relying too heavily on new immigrants to replace the native-born population, and reasons (especially given Mexican birthrates) to suspect that a steady supply of immigrants may dry up down the road.

Teixeira applies the same rhetorical sledgehammer to Last’s carefully-researched, copiously footnoted and even-handedly argued book that he deployed against Trende: “If Last’s claims sound hysterical and overwrought, that is because they are….If Last’s claims about the impending population crash are fanciful, his claim that fertility decline will lead to economic collapse is completely ridiculous.” But as with his attack on Trende, Teixeira’s assertions don’t stand up well under scrutiny.

To begin with, Teixeira’s review of the book is astoundingly parochial: something like half of the book and scores of its examples (both anecdote and country-level data) look at birthrates around the world and in history, and a good deal of Last’s argument addresses how the U.S. will be impacted by demographic changes in other countries, some of them very dramatically underway. But aside from one hand-waving reference to UN projections (more on which below) and a reference (which Teixeira refuses to engage) to Last’s reliance on slowing Mexican population growth, Teixeira completely ignores everything happening outside the United States and all the book’s discussion of history as an example.

Teixeira accuses Last of being “truly the man with a hammer who sees nails everywhere,” yet the entirety of his critique of Last’s solutions is to ask, “why not support immigration reform, as well as generally higher immigration levels?” and accuse him of being an immigration restrictionist who “just isn’t very interested in seeing more immigrants in the country.” It seems Teixeira is the one who only has a hammer, given that the argument for more immigration and growing political power for Democratic-leaning Hispanics is also the entirety of his attack on Trende, his attack on the 2004 polls and the 2002 book that made his name. As Last noted in response, if you actually read the book, you’d see that Last is not arguing against more immigration, just explaining why it’s not the whole answer to every problem.

As for number-crunching, Teixeira didn’t even bother to grapple with Last’s marshalling and sifting of the demographic data; he just appeals to authority:

The Census Bureau does project that the fertility rate will diminish, but only by a modest .09 over the next 50 years. And while the fertility rate is likely to remain below the replacement rate for the next 50 years, the Census Bureau expects us to add another 100 million people by 2060 due to immigration and “demographic momentum.” (Despite sub-replacement fertility rates, a relatively large proportion of the population will be in prime reproductive years for decades to come.) So much for population collapse.

Last is similarly off base in his projections for the rest of the world. He sees global population decline…The U.N. Population Division begs to differ. According to their 2010 projections, the countries with the lowest fertility rates today – typically, more developed countries – should see fertility rates rise somewhat over the century and converge with rates in less developed countries.

At least this time, Teixeira looked at what the Census Bureau had to say. But he offers no reason why we would expect declining fertility rates to reverse themselves down the road, and while Last explains the implausibility of the UN’s 2010 projection (which represented an abrupt and not credibly explained about-face from its prior stance), Teixeira incuriously accepts it at face value and then asserts these inherently speculative projections as fact. Last himself admits that many of the future projections involve uncertainty – but the past and current trends are hard facts. As Last notes, this is far from the only area in which Teixiera just hand-waves whole detailed sections of the book – unlike Teixeira, Last actually considers the experiences of other countries to see what works and what does not, rather than just blithely assuming that demographic trends will reverse themselves of their own accord.

Liberal pundits and Democratic activists – and the line between the two can be hard to locate – have increasingly overinvested in two excuses for insulating themselves in a bubble: that no data can possibly support any arguments by analysts on the Right, who can be dismissed with an ad hominem, a quick hand-wave and a lot of nodding, and that demographics alone will deliver them a permanent electoral majority without the need for their side to actually win any more arguments. These are hazardous trends, and the imbalance between Teixeira’s rhetoric in dealing with pundits like Trende and Last and the actual substance of his critiques is an illustration of the dangers of the need to sustain this illusion at all costs to a writer’s own credibility.