RS: Donald Trump Tries To Backtrack After Insulting Iowa Voters As Brain-Damaged Corn-Huffers

“Will this be the gaffe that finally sinks Donald Trump” has been a popular parlor game for some months now, and while polling shows that Trump is accumulating unfavorables and hard-core opponents in Iowa and seems to be stalling in persuading any additional supporters, his long-awaited collapse in the polls has yet to materialize and increasingly looks like it is more likely to be a gradual bleed than the implosion of a supernova. Thus, Trump has survived insulting Sen. John McCain (R-AZ)’s war service, badly misunderstanding Christianity, making crude remarks about Megyn Kelly, going full 9/11 Truther, and repeatedly embracing far-left-wing talking points and positions on a whole host of issues.

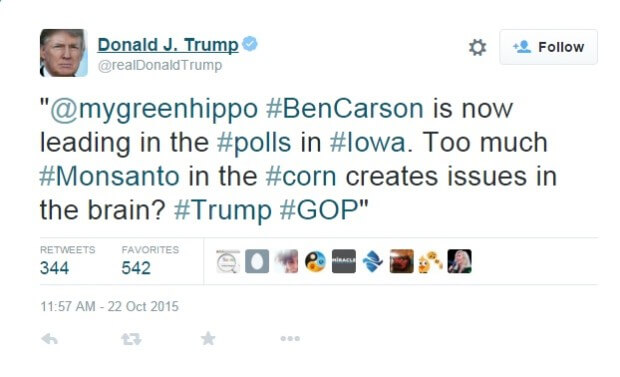

But in all Trump’s feuds, smack-talking and insults, the one thing he had not done previously was insult the voters. Until today:

“@mygreenhippo #BenCarson is now leading in the #polls in #Iowa. Too much #Monsanto in the #corn creates issues in the brain? #Trump #GOP“

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 22, 2015

“@mygreenhippo #BenCarson is now leading in the #polls in #Iowa. Too much #Monsanto in the #corn creates issues in the brain? #Trump #GOP”

Now, if you’re not real familiar with Twitter, this is not Trump’s own words – he is quoting, with apparent approval for his audience of 4.6 million Twitter followers, a tweet by a Twitter user named @mygreenhippo whose Twitter bio links to the website http://www.sexaddiction.tv, a link I dare not click on to find out what it leads to. But leave aside who the original tweeter is (two weeks ago Trump retweeted a Dutch white supremacist, which is sadly characteristic of a small but extraordinarily vocal subset of his online fans) – I’m quite sure that Trump pays no attention to the identity of people tweeting at him, and while doing so would be the wiser course, it’s not really his responsibility to investigate.

But Trump rather clearly was endorsing the sentiment: that Carson pulling ahead of him 28-20 in one poll (the latest Quinnipiac Iowa poll, the first Iowa poll in three weeks) means that something is wrong with Iowa voters, who have therefore earned a vintage Trump put-down. If you think insulting the voters of Iowa is no small deal, ask former Iowa Congressman Bruce Braley, whose bid for the Senate last year was dramatically upended by video of him deriding Chuck Grassley as an Iowa farmer. Or ask Scott Walker, who in March fired strategist Liz Mair over tweets critical of Iowa’s caucus and voters that predated her hiring by Walker. Maybe Trump genuinely shares this level of scorn for Iowans – the man’s a Manhattan real estate mogul, after all, and his speaking style suggests a man who believes he is always putting one over on you – but just as likely, he was just slipping into his typical pattern of handing out schoolyard insults to anyone who disresepects The Donald.

Moreover, the tweet in question showcases a second of Trump’s unsavory characteristics, his tendency to embrace any old conspiracy theory, in this case fear of Monsanto-produced GMOs, a popular bugaboo on the anti-science Left. Smearing the voters and diving into the left-wing fever swamps is an impressive twofer.

Perhaps recognizing that this was a disastrously poor decision, Trump – who is famous for never apologizing for anything – three hours later offered the closest to an apology he is likely to deliver in this campaign:

The young intern who accidentally did a Retweet apologizes.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) October 22, 2015

The young intern who accidentally did a Retweet apologizes.

Now, while many politicians do indeed have interns tweeting, Trump has rather clearly been doing his own, unfiltered and in his own distinctive voice, for years now, and has given off every indication in interviews that he’s the man with his finger on the Tweet button. Maybe the tweet was an intern’s tweet, maybe not, and maybe the “apologizes” is intentionally tongue-in-cheek a la Monty Python, but characteristically, Trump won’t take responsibility directly for anything.

Maybe the more interesting question is whether we will see more of this kind of reaction as more bad polling news arrives in the future. As Noah Rothman notes, Trump’s campaign message at this point is hugely dependent on bragging about the polls, such that bad polling news could feed on itself and undermine the whole basis of his appeal:

Much of Trump’s extemporaneous stump speeches focus on his roost at the top of polls of Republican primary voters. He contends ad nauseam that the United States is in decline and does not “win anymore.” You’re expected to accept the premise and choose not to ask for specifics about what has been lost in the ill-defined contest. “We’ll have so much winning, you’ll get bored with winning,” Trump adorably quipped…Tragically for Trump, however, he might soon be robbed of his claim to be the bearer of endless victories. This leads us to the big question: Can the Donald Trump campaign endure a loss?

Jeb strategist Mike Murphy – even discounting for his obvious self-interest – makes a similar point:

[N]othing changes like momentum from polling. I often joke that if I ever had the horrible, malicious job of being Head of the PRC’s Intelligence Service and they said, “All right, here’s $20 billion, screw around with the U.S,” one of the first things I’d go do is bribe media pollsters. because you totally control the thinking of the D.C. press corps based on polls. Right now, if four polls had come out saying Trump at seven and Jeb at 29, all the media commentary—without either guy changing a thing they’re doing—would be the exact opposite. Well, Jeb’s low-key style is clearly resonating with voters, it’s exactly what people are looking for, I can just hear it now. Well, Trump’s bombastic style clearly has backfired, we could see… And by the way, the same people would be totally comfortable completely switching their opinions in a minute because most of them are lemmings to these, in my view, completely meaningless national polls.

Walker 18.8

Bush 9.0

Paul 8.5

Trump 8.5

Carson 8.3

Huckabee 7.5

Cruz 7.3

Rubio 6.8

Santorum 4.3

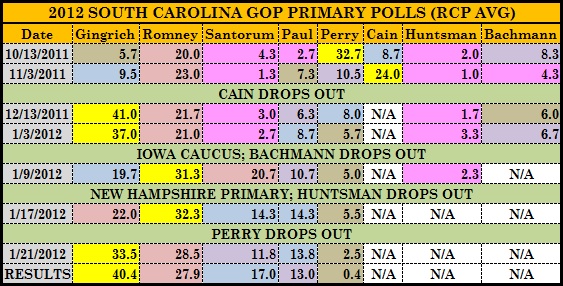

Today, Walker is out, and Jeb, Paul, Huckabee and Santorum are down to less than half their poll averages from late July. In 2012, when the Iowa Caucuses were a month earlier (January 3), Herman Cain was over 30 in the RCP average in late October, Newt Gingrich was at 31 on December 11, and on December 26, 2011, Rick Santorum stood in sixth place at 7.7% of the vote. Yet Santorum won. And if Iowa polls are dicey and volatile, national and later-state polls are even more useless, in part because they are affected by what happens in Iowa and New Hampshire. The Washington Post’s “Past Frontrunners” list notes the national poll standing at this point of the race of some past frontrunners who went on to lose:

2004: Wesley Clark +5

2008 (D): Hillary Clinton +27.3

(R): Rudy Giuliani +9.2

2012: Herman Cain +0.5

And look at what happened in the South Carolina polls in 2012 after Iowa and then New Hampshire:

Here, there are reasons to think more bad news in Iowa may be headed Trump’s way, which could wash out the last 0.7 points of his lead in the RCP average in Iowa. Rothman notes that Iowa is the one place where Trump actually has negative ads running against him, a $1 million Club for Growth ad campaign (I noted last month that the Summer of Trump poll surge was partly dependent on the fact that nobody was in the field running ads yet). And organizing is key in Iowa, yet Trump is the only candidate in the race who hasn’t even bothered to purchase a voter file, and his “campaign has spent more on hats and T-shirts than on field staff members in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina.” So likely-voter screens alone may sap his standing as the polling grows more rigorous. The most respected gold-standard Iowa pollster, J. Ann Selzer’s DeMoines Register poll, will be announcing the results of another Iowa poll Friday, and if it similarly shows Trump out of the lead, it will bear watching if he has another spasm of lashing out at the voters.