RS: Marco Rubio’s Path To Victory After Super Tuesday, By The Numbers

Mister One on One

Super Tuesday ended up not being quite so super for anyone in the GOP primary. Donald Trump was supposed to break out and put the race away, and instead lost 4 states, won 3 more by narrow margins, and looked very much like like a beatable frontrunner, including a 17-point thumping in the biggest state in play. Ted Cruz saw his “SEC firewall” melt, finished third with fewer votes than Marco Rubio across the South, and faces a long march into far unfriendlier territory. Rubio narrowly lost Virginia after staking much of his Super Tuesday campaign on staging yet another of his furious late comebacks there, got clobbered in the delegate race even in states where he got a lot of votes, and generally continued his pattern of closing well without quite putting away his opponents. John Kasich lost his shot at his first primary win, losing Vermont by 2.3 points, and finished dead last behind Ben Carson in 7 out of 11 states. And Carson, despite finally cracking the elusive 10% barrier in two states, won delegates only in Virginia and was finally compelled to conclude he must drop out.

Let’s take a look at the lessons of Super Tuesday, as well as what they tell us about the GOP’s best choice for consolidating behind a single anti-Trump candidate, which now seems as if it will not happen until after Armageddon Tuesday on March 15. I continue to believe, for reasons both quantifiable and unquantifiable, that Marco Rubio is the best man for the job.

Marcomentum, Big Texas and the Anti-Trump Turnout Boom

All the talk heading into Super Tuesday was about Donald Trump’s “ceiling”: would he remain stuck at about a third of the vote, as he was in the first three states, or would he start cracking the 40% thresholds that signalled a “jailbreak” of follow-the-frontrunner voters to Trump?

Trump did manage to hit full jailbreak status in two states, Massachusetts (49%) and Alabama (43.4%), and perhaps more distressing to the anti-Trump forces, got close in two other states whose politics are less of a one-party cesspool, Tennessee (38.9%) and Georgia (38.8%). But his overall share of the vote was 34%; in five states he fell below a third of the vote (Arkansas, Vermont, Oklahoma, Texas and Minnesota), in the last three of those below 30%. Of his seven wins, three were by fairly close margins of victory:

Virginia: 34.7% to Rubio’s 31.9%, a margin of 28,918 votes. John Kasich, who finished fourth, drew 96,519 votes in Virginia (9.4%), and Ben Carson, who finished fifth, got 60,093 (5.9%); it’s not hard to see that the minor candidates made the difference, especially Kasich, whose appeal is so different than Trump’s (Kasich is pitching to voters who are both ideologically and temperamentally moderate, while many of Trump’s voters are the former but few are the latter).

Arkansas: 32.8% to Cruz’s 30.5, a margin of just 9,271 votes. Carson, who finished fourth, got 23,173 votes (5.7%), while Kasich got 15,098 (3.7%). Again, even before you discuss the Rubio/Cruz divide, it’s clear that the minor candidates were a drag on the anti-Trump movement.

Vermont: 32.7% to Kasich’s 30.4%, a margin of 1,424 votes. Carson, who finished fifth, got more than that – 2,544 (4.2%).

So on top of the four states where he was beaten, including a 17-point loss to Cruz in Texas and a 15-point loss to Rubio in Minnesota, Trump has hardly put this race away. If you could combine the Rubio and Kasich votes and the Cruz and Carson votes, Super Tuesday would have looked like this:

Texas: Cruz 47.9%, Trump 26.7%, Rubio 22.0%

Oklahoma: Cruz 40.6%, Rubio 29.6%, Trump 28.3%

Arkansas: Cruz 36.2%, Trump 32.8%, Rubio 28.6%

Alaska: Cruz 47.3%, Trump 33.5%, Rubio 19.2%

Virginia: Rubio 41.3%, Trump 34.7%, Cruz 22.8%

Minnesota: Rubio 42.4%, Cruz 36.3%, Trump 21.3%

Vermont: Rubio 49.7%, Trump 32.7%, Cruz 13.9%

Georgia: Trump 38.8%, Rubio 30.0%, Cruz 29.8%

Tennessee: Trump 38.9%, Cruz 32.3%, Rubio 26.5%

Alabama: Trump 43.4%, Cruz 31.3%, Rubio 26.5%

Massachusetts: Trump 49.3%, Rubio 35.9%, Cruz 12.2%

If we had those results, all the talk Wednesday morning would have been about a Trump collapse. Now, obviously you can’t just allocate the minor candidates’ support like that going forward – some will go unpredictably between Rubio and Cruz, some to Trump, and – this is important to remember – some will just stay home, because they were just personally loyal to Ben Carson or because Kasich is selling a pure-moderation message that none of the other candidates are selling. It is probably the case, for example, that a good number of Kasich’s New England open-primary independent supporters would just not have voted in the Republican primary if the choices were Trump, Cruz or Rubio; a significantly higher percentage would probably have skipped it if the choices were just Trump and Cruz, given how many Kasich-style moderates regard both of them with roughly equal horror. But as Sean Trende has demonstrated with a deep dive into the exit polls I won’t rehash here, the demographic profiles of Kasich and Rubio supporters in this race are pretty closely aligned, as are the demographic profiles of Cruz and Carson supporters. Leon made the same point this morning in sketching out what Cruz would need to do in order to be the anti-Trump candidate.

Also, for all the talk about Trump driving the record-breaking turnout we’ve seen in state after state so far – Vermont and New Hampshire are the only states where turnout wasn’t up at least 20% from 2012 – there is another side to the story: in the 11 Super Tuesday states, even if you don’t count a single vote for Trump, turnout was 119.1% of 2012 turnout in those states (thus, up 19.1%); across all 15 states to vote so far, the figure is 113.3%. That’s partly due to a turnout boom for favorite son Cruz in Texas (up 43.1% without Trump voters) and significantly due to having a contested election in Virginia, where Mitt Romney’s opponents failed to make the ballot in 2012 (up 151.9%). But anti-Trump – or at least non-Trump – turnout has been greater by itself than 2012 turnout in six other states as well: Iowa (+16.4%), Nevada (+22.9%), Oklahoma (+15.1%), Arkansas (+79.4%), Minnesota (+81.5%) and Alaska (+10.6%). Whether those are voters coming out because they want to stop Trump or because they are excited by his opponents, that’s great news for the GOP’s chances of surviving Trump’s attempt at a hostile takeover.

Another sign that Trump can be taken – but that time is starting to run short – is that yet again, he fared relatively poorly among late-deciding voters. On the other hand, he did not do as poorly with late deciders as he did in Iowa or South Carolina, and he actually won them in Massachusetts and Alabama, as he had in New Hampshire), leading to his jailbreak wins there. Rubio, meanwhile, remains easily the best closer in the bunch: he’s now won late-deciding voters 7 times, winning them by double-digit margins in Nevada and Virginia and beating Trump by double-digit margins in Iowa, South Carolina, Oklahoma and Arkansas. Cruz won late deciders in Texas and Tennessee, Kasich in Vermont:

Note that we don’t have entrance/exit polling for Rubio’s win in Minnesota or Cruz’s in Alaska, both caucus states.

The late charge accounts for Rubio’s fairly persistent overperformance of his polls:

Rubio outperformed his RCP average in Minnesota (14 points), in Virginia (10 points), in Oklahoma (5 points), in Arkansas (2 points), in Vermont (2 points), in Tennessee (2 points), and in Georgia (1.5 points).

That’s reason to be optimistic about Rubio going forward as the standard-bearer of the anti-Trump faction, but it’s also worrisome how far ahead Trump has been with the two-thirds or so of the electorate in each state that decided their votes more than a week in advance (Cruz in Texas is the only candidate besides Trump to win early deciders, and the massive size of his lead with them suggests that perhaps Rubio would have been wiser not to bother contesting Texas, where he got over half a million votes and 4 delegates).

Geography

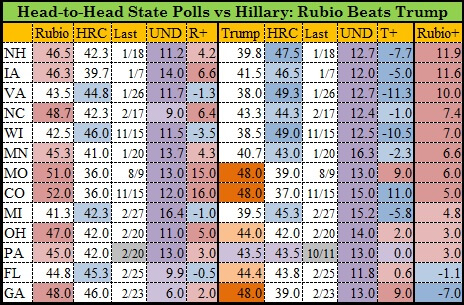

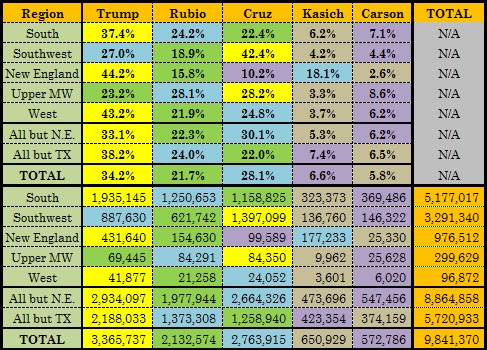

The good news for Rubio is that yet again, he proved the breadth of his appeal across the map. He continues to be the only candidate besides Trump who is running a 50-state campaign. With all the votes counted aside from a few very late precincts in Arkansas and Minnesota, we can see that outside of Cruz’s home state of Texas, Rubio got 114,000 more Super Tuesday votes than Cruz did – 1,373,308 votes at last count (24.0%) to Cruz’s 1.258,940 (22.0%). That’s swamped by Cruz’s big showing in his home state, where he got nearly as many votes (1,239,158) as Trump and Rubio combined (1,259,669), such that if Trump ends up with the nomination, Texas Republicans may be printing “Don’t Blame Me, I’m From Texas” bumper stickers, and justifiably so. But it underlines the extent to which Ted Cruz depends on a particular type of voter that may be harder and harder to find in the states ahead of him than the states behind. Texas really is different.

Let’s break down the voting so far by region, grouping states that may have something politically in common. The largest region to vote so far is the South, the states below DC and east of Texas: Virginia, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee and Arkansas. This region is now pretty far into being done voting; Louisiana votes March 5, Mississippi and Kentucky on March 8, Florida, North Carolina, and Missouri March 15, and only one culturally quasi-South state left after Armageddon Tuesday: West Virginia May 10.

Then we have the Southwest, of which Texas and Oklahoma voted on Tuesday; Arizona votes March 22, New Mexico on June 7 at the very end.

New England is three states in – New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Vermont – with Maine voting March 5 and Rhode Island April 26.

Two Upper Midwest states have voted, Iowa and Minnesota, both caucus states; Wisconsin votes April 5.

Two states in the West have voted, Nevada and Alaska, both caucus states; Hawaii votes March 8, Oregon May 17, Washington May 27, and California June 7.

The other regions aren’t in play yet:

The Great Plains states start March 5 in Kansas, followed by North Dakota on April 1, Nebraska May 10, and South Dakota June 7.

The Atlantic Northeast states, DC on March 12 and then New York April 19, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Connecticut and Delaware April 26.

The Mountain states were supposed to begin Super Tuesday, but Colorado cancelled its voting and Wyoming pushed back its delegate selection to March 12; Idaho kicks off March 8 followed at long intervals by Utah March 22 and Montana June 7.

The territories start March 6 in Puerto Rico, and the others (all small) vote between March 12-19.

And of course the Midwest, which begins with Michigan March 8, Illinois and Ohio march 15, Indiana May 3. Along with the Northeast, California and Florida, the Midwest is highly likely to decide the nomination.

So how have the candidates fared in these regions?

Cruz’s entire popular vote lead over Rubio consists of his margin in Texas. He has cleaned up two states in the Southwest, but Arizona is the only big delegate prize left there, and Rubio just snagged the endorsement of New Mexico Governor Susanna Martinez.

If you had told me a few months ago that Rubio would get nearly 100,000 more votes than Cruz in the South, I’d have been sure that we’d be talking today about the Cruz campaign in the past tense. Rubio finished well ahead of Cruz in Virginia, and beat him very narrowly in South Carolina and Georgia. That was largely due to Trump eating into what was supposed to be Cruz’s voters, killing Cruz’s plan for an early knockout blow. Of course, this primary season has laid waste to a lot of plans (both Cruz and Rubio at various times floated the idea of South Carolina being a critical early win), and here we are. The March 5-15 states left in the South will likely go a very long way towards determining which of Rubio or Cruz stays in this race to the end.

Cruz also pulled just slightly ahead of Rubio in the Upper Midwest, by 59 votes pending the final vote tally in Minnesota, so that’s more or less a wash. We have not yet had a primary in the Upper Midwest, although Wisconsin is more similar to Minnesota than to Iowa, and the last two Marquette polls had Rubio running a little ahead of Cruz but Trump starting to widen his lead.

On the other hand, boding poorly for Cruz’s ability to go national, he has been a complete non-factor in the New England states, whereas Kasich – who has finished behind Ben Carson in 9 of the 12 states outside New England – has won just 5.3% of the vote outside those states and 3.3% in the Upper Midwest despite being the most Midwestern guy in the field.

The West is the hardest to figure, since we have two small, oddball caucuses to work with, one of which (Nevada) was dominated by the fact that Trump owns a huge Vegas casino and is one of the state’s most prominent employers.

The geographic case for Rubio is simply that he’s the only guy besides Trump who doesn’t have to write off any regions. The downside of that, so far, is that in a divided field he’s been stretched thin in ways that don’t help him accumulate delegates; in South Carolina, Texas and Alabama he got a combined 827,633 votes (22.3%, 17.7% and 18.6%) and got a grand total of 5 delegates to show for it, because South Carolina was winner-take-all and Texas and Alabama had 20% minimum thresholds for getting any statewide proportional delegates. Rubio got more actual votes in Georgia than Cruz, but lost the delegate race to him there, 18-14. He could face the same situation in Louisiana, if the early polling is suggestive (it may not be).

Demographics and Ideology

Let’s return to a point I made in the wake of South Carolina: Ted Cruz’s success in the early states has been really, really, really dependent on (1) Evangelical Christian voters and (2) self-described “Very Conservative” voters. And neither of these groups is likely to be anywhere as prevalent once we get past March 5.

Here’s a weighted average (by the size of each state’s vote) of what the exit polls show us about Cruz’s dependence on Evangelicals, highlighting in the third column the % of each state’s voters who were Evangelical in the exit poll samples (again, we have no exits for Minnesota or Alaska):

That looks pretty lopsided – Cruz runs about even with Trump with about a third of Evangelical Christians, with Rubio drawing a little under 20% and Kasich a rounding error. Among non-Evangelicals, however, Rubio runs six points ahead of Cruz, who drops to a little over half of Trump’s vote, and Kasich draws the difference between Rubio and Trump.

But wait! You will notice that there was one very large group of non-Evangelicals Cruz did manage to do well with: Texans, who gave their hometown hero 31%. (I should note that even if he doesn’t win the nomination, Cruz’s powerful showing in the Texas primary should deter anyone from challenging him in 2018 on the theory that Texans might have soured on him). If you look at the 12 states outside Texas where we have exit polls, Cruz only cracks 20% of the vote in one of them (Alabama – which among the 9 states where the exit poll question has been asked so far, is the only one where more voters would prefer deporting illegal immigrants to ‘amnesty’).

While Cruz supporters may object to separating out Texas, the simple fact is that the pattern is really consistent outside Texas, and Texas only votes once. In the rest of the states, he barely runs ahead of Kasich with non-Evangelical voters, and runs more than 10 points behind Rubio, while Rubio runs only 4 points behind Cruz with Evangelicals. Plus, he does even worse with non-Evangelicals in non-Southern states, even border-South states like Virginia. Cruz simply has not solved this problem, and given Trump’s strength outside of the Evangelical vote, it would seem rather risky to pick Cruz as the chief vessel for the anti-Trump vote headed into a whole bunch of states where his core voting bloc is a lot smaller part of the electorate (sort of like how Bernie Sanders ran into a completely predictable buzzsaw when he got out of states with an overwhelming number of white liberals):

If you’re wondering, those numbers probably do understate the Evangelical vote a bit – comparing the projections I drew on for my last post to actual results:

That’s good news for Cruz, but it may not be enough – massive Evangelical turnout helped him pull away from Rubio in Tennessee, Alabama, and Arkansas, but still didn’t carry him to victory against Trump.

Then there’s the ideological splits, with Texas:

…and without Texas:

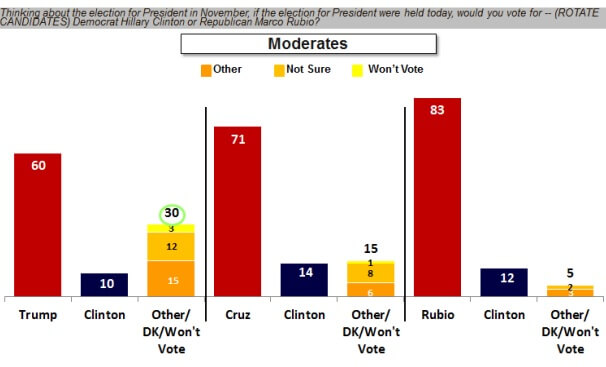

It’s the same pattern: Cruz did vastly better with “Somewhat Conservative” and Moderate voters in Texas than in the other 12 states, and when you back out Texas, you see that Ted Cruz voters are from Mars, John Kasich voters are from Venus…and Rubio occupies the sweet spot in the middle (a nicely habitable planet), beating Kasich with the moderates (where Cruz is in single digits), getting about half of Cruz’s vote with the Very Conservative voters (where Kasich is roadkill), and getting more of the largest group – the Somewhat Conservative voters – than Cruz and Kasich combined. And outside Cruz’s 57-23 margin in Texas, he only beats Trump by a point among the one group he has to depend on.

Cruz has unsurprisingly done best in states where Very Conservative voters are around 40% of the vote – his wins have come in Iowa (40%), Texas (39%), Oklahoma (43%) and Alaska (no poll). Among the upcoming states for which we have 2012 exit polls from contested primaries/caucuses (i.e., before Santorum dropped out and effectively ended the race), most of them will have more moderate electorates. Share of Very Conservative voters, 2012 exit polls:

Louisiana 49%

Mississippi 42%

Arizona 34%

Florida 33%

Ohio 32%

Wisconsin 32%

Michigan 30%

Maryland 30%

Illinois 29%

Again, these are mostly not good numbers for Cruz, even assuming a bit of an upward shift.

Completing the exit picture, let’s look at party self-ID, bearing in mind that this may vary from actual registration (even closed primaries like Oklahoma feature people who don’t call themselves Republicans:

…and without Texas:

You can see once again that Cruz’s candidate profile looks quite different in Texas than everywhere else. His showing with independents varies a lot because, well, Massachusetts independents are pretty moderate, whereas, say, Nevada independents trend libertarian. Closed primaries are likely to hurt Trump, as Neil Stevens showed in detail earlier today, but it’s far from clear that they help Cruz more than they help Rubio. What is clear is that they starve Kasich of oxygen; while he did well with Republicans in Vermont and passably in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, his ability to even appear on the map in places like Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia depends on independents. Which also suggests that Kasich’s inevitable departure from the race may not leave a whole lot of voters on the table in the 26 (out of 40) remaining contests with closed primaries or closed caucuses.

Conclusion

Many of us had hoped that Super Tuesday would winnow the field a good deal more, because Trump’s success thus far has depended on a divided opposition, and the longer he can sustain that (as Romney did in 2012), the more he builds the psychology of a winner. It now looks as if that will have to await Florida and Ohio on Armageddon Tuesday, unless something really surprises us before then. As Phil Klein has illustrated, the calendar slows a lot after that, giving the remaining contender(s) a lot more time to pound Trump, slow his march to 1,237 delegates, and possibly either get their themself or (much more likely) throw this to a contested convention where the party will have a final chance to come together and save itself from Trump and certain defeat.

Rubio will – as he has on several occasions – now have to prove himself again, starting Saturday (where Kansas may be his best bet, although we have little useful polling, and Rubio is further ahead of Cruz in the one poll we have for Kentucky) and running through Florida. But on the morning of March 16, we’ll be looking once again for an opportunity to end Trump’s ability to win with 34% of the vote. It won’t be easy to convince two of the three candidates to leave, and it may be especially challenging for Rubio to do because playing chicken, not making deals and frustrating the Republican Party are three of Ted Cruz’s favorite pastimes. Which is why Rubio will really need to put on a convincing showing that his ability to compete in more places and with more groups than Cruz is a vital asset.

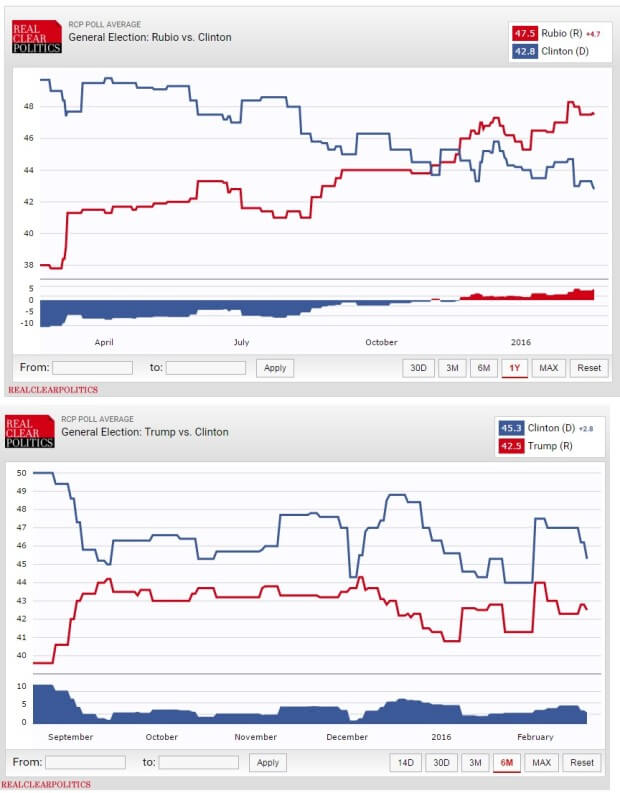

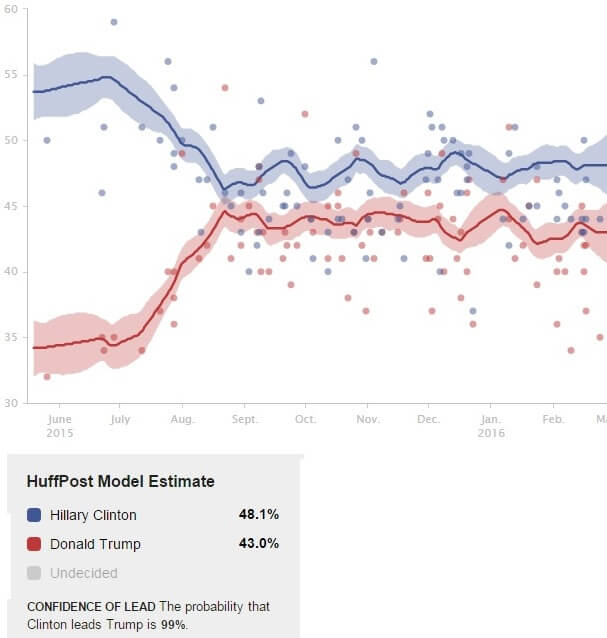

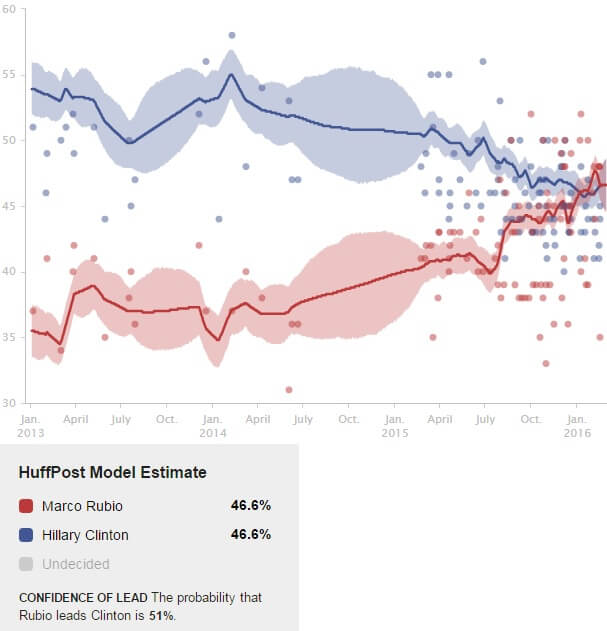

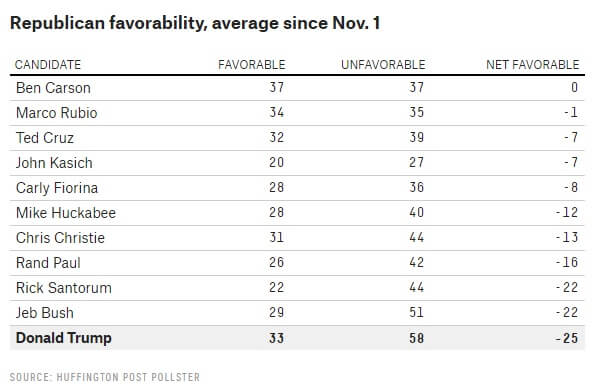

The case for Rubio being the guy who can ‘unite the clans’ and beat Trump is fairly straightforward: Cruz has no record of competing for the Kasich voters (or the similar voters who make up a faction of Rubio’s base), and Kasich has no prayer of getting Cruz’s voters. Cruz abandons blue areas like New England and probably a lot of the Northeast; Kasich abandons most of the rest of the country other than Ohio. Rubio fights everywhere. Cruz’s argument is that a lot of his voters, but not Rubio’s, would go to Trump – but as with the Carson voters, voters who are released from the guy they were backing are apt to be persuadable, and Rubio has the best record of closing well with late deciders, and would benefit from staging a one-on-one race where (as has only just happened since Nevada) some serious fire is concentrated on Trump. And certainly Rubio can present a very vivid contrast to Trump.

The theme of Trump’s campaign has been his ability to avoid a one-on-one race. The theme of Rubio’s, as in his 2010 Senate race, has been all his opponents’ fear of the potential of finding themselves one-on-one with him.

It’s still the best way to beat Trump: rally around one guy who can play on the whole map, with the whole party.